Dr. Moeed Pirzada | Pique Magazine |

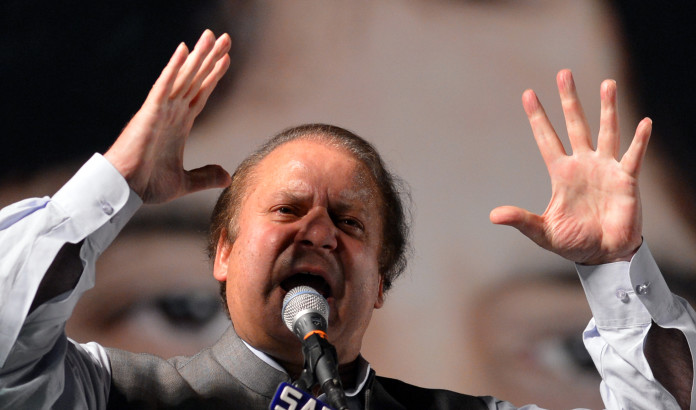

It was early 2006; I was in a small office at the backend of 10-Duke Street, not very far from Selfridges and looking straight onto his face. Seated across the table was someone most of us in London readily agreed will once again be the future prime minister of Pakistan. Question was: when, how and with what kind of compromises? This was a few days after Nawaz Sharif’s landing at Heathrow from Jeddah, and after his much talked about speech at Slough, some distance from Heathrow, in which he had thundered that military has no role in Pakistani politics; someone had to decide that and today we have taken that position. Did people, or even his supporters believed that? South Asian politicians say many things and we all have learnt to treat these pronouncements as raindrops. How could this be different? And besides that, you need to keep in mind: this was just the beginning of 2006, Musharraf was still firmly in the saddle, elections were being talked about in the remote future with a degree of disbelief and there were other issues- many other issues.

I was meeting him on a single point agenda. Someone very intimate with him – and someone who trusted my research- had asked him to listen carefully to the timeline of Benazir’s meetings with U.S. officials and politicians, and with the interlocutors of Musharraf and her growing resurgence on the international scene. Apart from Nawaz Sharif and myself there were just three persons in that small room; all very close confidants. As I explained with the help of sources and dates he listened patiently and carefully; all the time picking up salted nuts from a small plate perched on the table in front of him. When I finished, he made a long pause and then said, more or less in these words:

“I don’t know if she is really doing it or not, but if she is doing it then she is doing a mistake and I have decided that I won’t do it again; I will sit in the opposition and wait” he went on to explain that he had been thinking hard in his days of torment in jail and isolation in Saudi Arabia and he has concluded that they (generals) use us one by one and he has decided not to give this space to them ever again, and he is going to impress this thing upon Benazir as well.

Others in the room looked uneasily at each other; some of them were genuinely anxious about what was then beginning to be perceived as a growing rapprochement between Musharraf and Benazir courtesy Washington and what it entailed for PML-N and its political fortunes – given that it was in political wilderness since Oct 1999. I never attached much importance to what Nawaz said, treating it more as a mood of the moment; a political antic needed to send the hard ball message needed for effective jostling and bargaining. Little did I realize that what I have heard will emerge as the defining principle of Nawaz Sharif’s politics and Pakistan’s political discourse in the years to come. A few weeks later we got the opportunity to cover the much talked about meeting at Rehman Malik’s residence on Edgeware Road between Nawaz Sharif and Benazir Bhutto and much was promised and published. But let’s not talk about it. That is known history.

Time flies. Much happened after that: Iftikhar Chaudhry’s discovery of conscience, Lawyers movement, Musharraf’s emergency, Dogar Cou-rts, BB’s assassination, Zardari era, Musharrraf’s near impeachment and resignation, PML-N’s long march, restoration of Chaudhry court, emergence of Imran Khan’s Tehreek e Insaf as a powerful player, 2013 Elections and all that. But throughout the Zardari era whenever media pundits and commentators gloated that look how Zardari the street smart magician has outmaneuvered Nawaz, and has turned him into a Punjabi leader restricted to Lahore: I could somehow remember that meeting in the Duke Street and I felt that perhaps more than any one’s smartness or prowess Nawaz is limited by his own convictions and principle and I could only respect him for that.

However this is now 2014; much water has flowed under the bridge, newer challenges of ideological terrorism, separatist insurgencies and urban warfare now confront the Pakistani state and society and amidst this burgeoning chaos the third Nawaz government will soon be completing its first year in power. Yet it appears that the old fear of the military as the enemy and the quest to subdue them into a corner supersedes every other national consideration and dominates the decision making process – reflected not only in the nature of Musharraf trial but in general order of setting priorities – to the extent that sometimes people wonder that who Nawaz perceives a bigger threat: Taliban or the Military.

PML-N has ruled several times; this is their third time in center and almost fifth time in Punjab. Many features of their government are known: emphasis on privatization, mantras of liberal economics and deregulation. In early 1990’s it was PML-N who initiated series of economic reforms that made Pakistan a more open economy than many others in the region. Pakistan could not benefit from such economic liberalization is a different story. But overall PML-N approach towards politics can be defined as “Visible Physical Structures”; creation of buildings, highways, bridges, under-passes and other mega projects which public can easily identify with material progress and which provide avenues for economic patronage of political allies and support bases. In its pursuit of concrete structures, PML-N is much impressed by Tayyip Erdogan’s AKP party in Turkey. Latter’s ascendancy over Turkish military especially seduces PML-N leaders; however AKP’s efforts to humanize Turkish society and its five decade old relentless struggle against the Turkish establishment is often ignored by PML-N – a party that started its journey in the lap of the military establishment.

Closer working relations with Saudi ruling family and a desire to normalize with India both politically and economically was much pronounced even in the 1997-99 Nawaz government. Similarly the patterns of reliance upon select coterie of bureaucracy, linkages with far right in politics, intolerance towards dissent of any form within the party or outside in the larger political field, and hypersensitivity to media censures; treating every critic as an enemy – are all well noted features and can also be seen in the third Nawaz government – though admittedly in a refined attenuated fashion.

What has been added this time is a visibly palpable desire to stay on the right side of the American policy in the region; a much pronounced desire to embrace India, avoidance of nineties style polarization in domestic politics and a replacement of PPP by Imran Khan’s PTI as the main political rival in the field. Though all major political parties support free trade with India, PML-N’s indecent haste and rush in trying to finalize the deal before the end of March (which couldn’t happen in the end due to resistance from the farming community, foreign office and media) reflected not a well-studied economic calculus but a broad political decision expected to earn brownie points in Washington, London and Brussels and to empower certain business communities and to roll back the influence of military and its linked political interests.

Fears and anxieties – both genuine and exaggerated – of PTI benefitting from any policy failures of the PML-N overshadow all approaches towards governance from fighting Taliban to laptop schemes to woo country’s burgeoning youth. Not only PML-N leaders but also its linked bureaucracy spends most of their time and energies with international community, donors and media ridiculing Imran Khan as immature, childish, and fanatic and convincing everyone that PTI is failing and is becoming unpopular.

However the most pronounced and the positive difference is a clear cut policy to avoid polarization in domestic politics. With Sindh, Baluchistan, KPK and Azad Kashmir all being run by different political set ups is not only a manifest of changed Pakistani political scene but also a reflection on PML-N’s growing desire and ability to work with opposition inside the political system. Both KPK and Baluchistan are good examples of this new found confidence. Though keeping PTI out of power in KPK would have been difficult or troublesome, making a well-meaning nationalist like Dr. Abdul Malik Baloch Chief Minister in Baluchistan and resisting all attempts from local PML-N leadership and allies to oust him are symptoms of a new redefined Nawaz Sharif. PPP government’s continuation in Azad Kashmir is another good example; despite its lack luster performance and a potential coup by local PML-N, Nawaz Sharif directly intervened to thwart coup against PPP because he was made to believe that PML-N coup against PPP’s AJK PM was being engineered with the blessings of ISI.

But behind all this new found political maturity lurks a fear that political polarization gives military an opportunity to become strong and interventionist. Though PML-N pundits have never publicly admitted any failures of governance during 1997-99 period; their sole argument is that Musharraf the idiot spoiled the great political and economic work which the party was embarked upon under the great leadership of Nawaz Sharif and had it not been for the adventurism of uncouth Musharraf and his generals the socio-economic history of Pakistan and South Asia would have been different. However it appears that privately PML-N, including Nawaz, are conscious of the fact that they had mismanaged the politics and had created political divides and polarization that allowed military to become the popular saviors in Oct 1999.

What Nawaz and his kitchen cabinet need is to rise above this limited vision of “avoiding political polarization” and to apply the same healing spirit to the larger national scene where newer players have replaced the old genies of military, PPP and religious parties. Nawaz does not afford the luxury of fighting the old battle of 1990s Pakistan in the changed realities of 2014. The quicker he understands the better it will be for him and for all of us.