Moeed Pirzada | Khaleej Times |

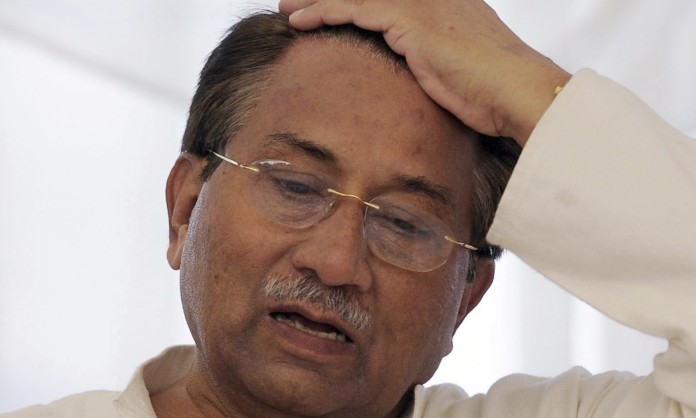

Gen. Musharraf, once the darling of the mini-screen, has gradually disappeared from the Pakistani television. Some days ago even the most primitive of the ships, the state broadcaster, was asked to dump him. But then last week he staged a comeback. And of all the screens, on Geo TV, his nemesis.

Geo had acquired the rights to Sabiha Sumar’s internationally recognised documentary: “Dinner with the President” Sabiha is a Pakistani but her co-producer Dr. Sathanathan is of Sri Lankan origins, working together they are able to fuse an internal view with an external comment.

The film was recently awarded the grand jury prize at the UAE film festival and short-listed at the Sundance Cinema Competition. But to most Pakistanis these were issues of secondary importance. To them, it was shocking that the hero of this cinematographic product whom narrator approached again and again in her quest to understand the country was Pakistan’s President: Pervez Musharraf.

Part of the answer lay in the fact the documentary was conceived at a time when he was indeed at the centre stage; but then all novels, films and documentaries deal with slices of history and end up raising questions.

Sabiha Sumar’s documentary serves an important function: It takes us back to an era in which Musharraf was the darling of the liberals and public at large was wary of the corrupt politicians. So we end up with at least two basic questions: One, was Musharraf ever really popular in Pakistan? And second, if yes, then how the maligned politician staged a comeback?

Reflecting back on all those years I think that we have to admit that Musharraf was at the crest of at least two waves of popular sentiments:

One, in October of 1999 when he kicked out Nawaz Sharif’s government that was constitutionally strong but had lost all political steam; Second, immediately after 9/11 when he was seen as a messiah by the chattering liberal classes for taking a quick decision to align himself with the United States against Taleban.

The American connection once formed Musharraf’s support base. But gradually it became his biggest liability as well as he was increasingly seen as an American stooge, perceived to be against the interests of Pakistan.

Ultimately, all governments and regimes suffer from anti-incumbency feelings, so there is hardly any point shedding tears for their demise. But for our understanding of the second question as to how politicians strike a comeback, it is important to emphasise that Musharraf’s popularity was essentially a function of the media, the civil society NGOs and liberal chattering classes. That is, in other words opinionated and opinion-making sections of the society but the politician’s support base remained intact backed by the chatter of these opinionated circles — thanks mostly to the feudal vote banks.

No doubt votes are almost always cast on local issues and affiliations but feudal vote banks are captured territories where large pockets of populations remain trapped in age-old narratives of religion, ego and respect. This becomes most obvious when we look at the PPP’s support base.

All negative discussions emanating from print and electronic media produced very little dents in the PPP vote banks in Sindhi and Saraiki belts; which may be disappointing to liberals like Sabiha Sumar who want democracy to be a tool for opening up the political landscape for change.

However, Nawaz Sharif’s vote bank represents somewhat of an interesting change and may be an indication of the times to come.

Even looking casually at the results of the 2008 elections we can see that Nawaz skilfully created a wave in the large Punjabi heartland from Pindi in the north to the Lahore in the South and up to Faisalabad.

A historian like Ayesha Jalal or political scientists at LUMS should study its real significance but I see an interesting pattern developing. In the United States, they use the term Bible belt, to allude to the influence of religion and televangelists. In the context of Pakistan we should consider a new term: “Media belt”.

Sharif seems to have derived support from areas clustered around the old GT road with large pockets of populations, which in the context of Pakistan, are more affluent, literate if not educated, upwardly mobile and also absorb the maximum impact of Urdu print and electronic media and thus have been the focus of the lawyers movement.

So can we argue that a new kind of voting belt is being created where people are more aware of the larger issues, of national causes and increasingly form opinions under the spell of Urdu media?

If this is true then the long term strategic importance of some media groups to make Lahore their operational base should be analysed seriously.

So whereas PPP is seen as a liberal party, because of the presence of better-educated, more anglicised leadership at the top, the likes of Aitzaz Ahsan, Sherry Rehman, Raza Rabbani and the support of the old left-leaning intellectuals in the print media; the overall vote bank of PPP is generally rural, more under-developed and isolated from the larger currents of consciousness. They persist with an internal narrative of Islam, ego, respect and gender roles that has not been penetrated effectively by the mass media.

But then this is the trend that may frighten many in the liberal circles. Sabiha Sumar’s documentary saw Sharif as the PM who was in pact with the Islamists to make the Holy Quran the supreme law of the land.

And I do hear the chatter especially by the Western and American diplomats that Nawaz and the PML (N) represent a sophisticated face of the Islamists. This fear may be exaggerated, especially when it is used as an assessment of Sharif or his associates, but has certain elements that are interesting.

Sabiha had identified her documentary as a personal journey; populations have political journeys. And when they move out of the stranglehold of feudalism, as Sharif supporters are doing — and as PPP voters will do at some stage — they pass through phases of nationalism or religious identities. The US diplomats and Pakistani liberals may be right in seeing a connection, and a continuum, between Nawaz Sharif’s support base and religious parties but they may themselves be responsible for pushing things in that direction.