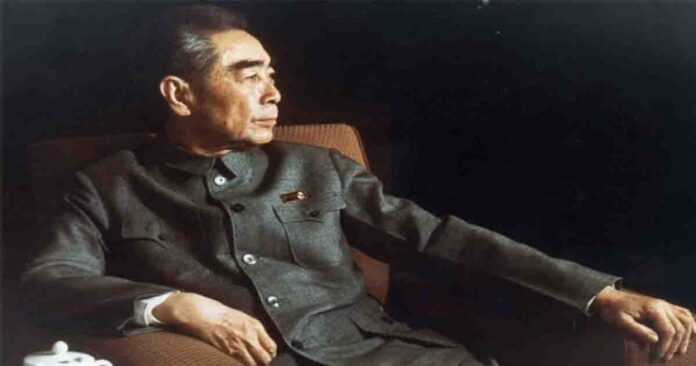

Zhou Enlai was the first Premier of the People’s Republic of China. This foreign policy wizard and one of the sharpest strategic minds of the 20th century was a great friend of Pakistan, so relations between the two countries moved from strength to strength during his time.

Pakistanis, who were adults in the 1960-70s, fondly remembered him as Chou Enlai, who first visited Pakistan in 1956. He is still known by older generations of Pakistanis by his transliterated name – Chou Enlai.

He befriended Pakistani leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (Foreign Minister, President, and PM), which endeared Zhou Enlai to generations of Pakistanis who remember him as one of the founding members of Communist China and a great revolutionary.

However, he was much more than that. Zhou Enlai remained an important member of the Chinese Communist Party from 1920 till his death in 1976. From October 1949 until his death in January 1976, Zhou was first China’s foreign minister and then it’s head of the government.

He served along with Chairman Mao Zedong and played a crucial role in stabilizing the Chinese economy and its strategic relations with neighbors and with the West. As a diplomat, Zhou served as the Chinese foreign minister from 1949 to 1958.

His earlier experiences of being a student in Japan and Europe and then serving the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) across Paris and Berlin (1919-22) were of great help to him in understanding the evolving global order.

Advocating peaceful coexistence with the West after the Korean War, he participated in the 1954 Geneva Conference and the 1955 Bandung Conference and helped orchestrate Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to China.

From historical documents released since then and the writings of Dr. Henry Kissinger, we all know that Pakistani leaders – Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Yahyah Khan – had played a crucial role in this Sino-American opening that changed the then global balance.

Zhou Enlai was the main force that helped devise policies regarding disputes with the United States, Taiwan, the Soviet Union (after 1960), India, and Vietnam. One may digress a bit to remind readers that Indian and western publications and research articles of 1960’s mocked Pakistani leaders for pretending as global balancers.

One such report, “China Report – Sino Pakistani Relations” published in 1965, still available at Sage Publications (Vol.1, Issue 4, July 1, 1965), makes fun of Pakistani President Ayub Khan for creating impressions that by befriending China, one of his goals is to bring China and the US close. And that Ayub Khan was trying to be a Pandit Nehru.

But while the world suspected Pakistani ambitions, Pakistanis did succeed in bringing China and the United States close. Zhou survived the turbulence of the Cultural Revolution, and while Mao dedicated most of his later years to political struggle and ideological work, Zhou was one of the main driving forces behind the affairs of state during much of the Cultural Revolution and is sometimes described as a figurehead of stability between 1949 and 1976.

Geneva Conference & Bandung

In April 1954, Zhou traveled to Switzerland to attend the Geneva Conference, convened to settle the ongoing Franco- Vietnamese War commonly referred to as the “Vietnam War” His shrewdness and his patience in view of arrogance displayed by US Secretary of State, Foster Douglas – who at one point had refused to shake hands with him – was credited with assisting the major powers involved (the Soviets, French, Americans, and North Vietnamese) to iron out the agreement ending the war.

According to the negotiated peace, French Indochina was to be partitioned into Laos, Cambodia, North Vietnam, and South Vietnam. Elections were agreed to be called within two years to create a coalition government in a united Vietnam, and the Vietminh agreed to end their guerrilla activities in South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

Decades earlier, at Nankai Middle School, a young Zhou Enlai was known for his theatrical performances; many had thought that he would end up becoming an actor. With his performance at the Geneva stage, Zhou Enlai had finally emerged as a Chinese leader on the world stage.

Bandung: The Asian–African Conference

Bandung, in 1955, was perhaps Zhou Enlai’s finest moment. He was a prominent participant in the Asian–African Conference held in Indonesia.

This conference in Bandung was a meeting of twenty-nine African and Asian states, organized by Indonesia, Burma (Myanmar), Pakistan, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and India, and was called largely to promote Afro-Asian economic and cultural cooperation and to oppose colonialism or neo-colonialism by either the United States or the Soviet Union in the Cold War.

At this conference, an important milestone of the changing post-colonial world, Zhou Enlai skillfully built a neutral stance that made the United States appear as a serious threat to the peace and stability of the region.

Zhou complained that, while China was working towards “world peace and the progress of mankind”, “aggressive circles” within the United States were actively aiding the Nationalists in Taiwan and planning to rearm the Japanese.

He was widely quoted for his remark that “the population of Asia will never forget that the first atom bomb was exploded on Asian soil.” With the support of its most prestigious participants, the conference produced a strong declaration in favor of peace, the abolition of nuclear arms, general arms reduction, and the principle of universal representation at the United Nations.

PM Zhou Enlai first visited Pakistan in January 1956 after a visit by Pakistani premier, Suhrawardy. In February 1964, Premier Zhou Enlai visited Pakistan for the second time, and in December, Pakistani President Ayub Khan visited China.

This tour of Zhou Enlai helped to further strengthen the Pak-China relations, various issues were thrashed, and new agreements of cooperation were signed, including the border demarcations between Pakistan and China.

It became obvious that China will not fight a war against the United States. Though since then, several Chinese leaders have visited Pakistan, for some reason, the name Zhou Enlai has fixed itself in Pakistani memories.

By the end of his lifetime, Zhou was widely viewed as representing moderation and justice in Chinese popular culture. Since his death, Zhou Enlai has been regarded as a skilled negotiator, a master of policy implementation, a devoted revolutionary, and a pragmatic statesman with an unusual attentiveness to detail and nuance.

He was also known for his tireless and dedicated work ethic and his unusual charm and poise in public. He was reputedly the last Mandarin bureaucrat in the Confucian tradition.