Policy Paper – Kashmir: Indian Strategic Initiative Since 9/11 and Imperative By Dr. Moeed Pirzada IPRI :: Islamabad Policy Research Institute

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 in New York laid the foundation for emerging new world order, to which both Pakistan and India reacted in haste. As Pakistan joined the US led coalition against its former ally Taliban regime in Afghanistan, to safeguard its national interests in a radically altered international scenario. A series of apparently inexplicable happenings, both in the Indian controlled state of Jammu and Kashmir and Delhi soon brought South Asia to the brink of a nuclear confrontation.

Kashmir emerged in the centre of this conflict where the separatist militancy suddenly became so explosive that it barged its way into the eye of international media at a time when the media’s undivided attention was focused on the war in Afghanistan. Before 9/11, relations between India and Pakistan were far from being warm and cordial but they were not actively hostile either. Since the stalemate at Agra Summit, a relatively placid atmosphere prevailed between the two nuclear neighbours. However, within a few days of the highly symbolic terrorist attacks on Indian Parliament, India had recalled its ambassador from Islamabad, banned its airspace to Pakistani air line, severed all land communications with Pakistan and with its troop mobilization, more than a million men faced each other, eye ball to eye ball, along the disputed borders in Kashmir.[1]

As international media discussed scenarios of a possible nuclear melt down in the sub-continent, Indian experts and media commentators predicted – and were in turn quoted by Pakistani commentators – that in the event of an Indian attack and thus war between India and Pakistan, US forces based in Pakistan will have to take out Pakistan’s nuclear capability to save the world from a nuclear Armageddon.[2] International emissaries from US, UK and EU paid a series of high profile visits to Islamabad and Delhi and pressure mounted on Pakistan to make concessions to India.

However, despite Pakistani concessions and promises to restrain the Kashmiri separatists and their Pakistan based supporters, India’s coercive diplomacy continued. Finally elections were held in the Indian controlled state of Jammu and Kashmir on a time schedule, surprisingly parallel to the elections in Pakistan. These elections were widely welcomed by the international community and media and robust international belief was palpable – even before the start of actual exercise – that these will be held free and fair and will help bring out a solution to the disputed state. In certain instances western countries made appeals to Pakistan that she should not interfere to fail the elections giving – in indirect way – credence to the Indian allegations that things do not return to normalcy inside J&K because of the Pakistani influence and interference.

Though reductions in troop deployments took place on both the sides after the elections in Kashmir, but the overall tension between two countries is far from over.

This paper examines the challenges faced by Indian strategic thinking after 9/11, vis-�-vis Pakistan; options available to it and responses offered. A detailed analysis of the sequence of events that appeared at propitious moments to help advance the cause of Indian strategy will be conducted to raise the question: “If there is something more to the nature of terrorism within India and Indian controlled Kashmir that meets the eye?” The response of international community notably US and UK will be also be examined.

Focus will develop on Kashmir, because the apparent aim of the Indian strategy was to win legitimacy for itself in the disputed Himalayan state where it is pitched against Kashmiri separatists for the last 13 years. However, paper will examine Kashmir in the broader contours of Indian diplomacy which, despite its apparent focus on the disputed Himalayan state, was actually threatened by the prospects of increased good will of international community towards Pakistan. It was seen by New Delhi as disrupting the emerging Indo-US road map; Kashmir being only a part of this strategy – albeit a very important one.

The paper will finally examine the convergence of external and internal imperatives that now drive US strategic alliance with New Delhi. Is there a way Washington can prevent it from becoming a “zero sum game” in South Asia? As US policy attempts to win tacit support for the Indian position that Kashmir is only its internal problem, does it realize the new challenges it creates for the Pakistani state – especially in the wake of Muthidda Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) gaining prominence in 2002 elections?[3] Is there a way US can build a close strategic alliance with India without jeopardizing its long-term interests in this region?

Indo-US Road Map After Kargil

Though the US “tilt” towards India, driven both by the changed geo-strategic perceptions and corporate interests, was becoming obvious throughout the 1990s but it was brought out sharply by the Kargil conflict in the summer of 1999.[4] From that point onwards, from India’s point of view a clear road map emerged for the future of US-India relations, independent of Pakistan and devoid of any shadows of Kashmir or talk of “Kashmiri self determination.”

By that time, India had more or less managed to overcome negative fallout, resulting from the human rights violations of its “brutal counter insurgency” in Kashmir. With the withdrawal of JKLF from armed resistance against India and the emergence of certain celebrated terrorist acts like the abductions of five western tourists by an obscure group Al-Faran in 1995, India had found it increasingly convenient to paint the insurgency in Kashmir as mainly a foreign sponsored terrorism.

The orchestrated domestic and international media campaign on Kargil bolstered by fiercely nationalistic Indian diaspora in major US and European cities and the chain of events inside Pakistan that ultimately resulted into the removal of the government of Nawaz Sharif by Pakistani military. These events led to severe shrinking of political space available to Pakistan in international arena. In this context it will be helpful to appreciate that Nawaz was widely perceived to be supported by the Clinton Administration in his power tussle with a nationalistic military that won’t compromise on his “vision for peace” by coming to some sort of accommodation on Kashmir.

Whether Nawaz had any viable vision on Kashmir and whether India was serious in any dialogue with Pakistan on Kashmir are besides the scope of this paper. What is important here is to appreciate that Nawaz was seen to be having the good will of Clinton administration against his own military.[5] And this apparent cleft provided immense happiness to Indian strategists who, for the first time saw a serious disagreement emerging between the civil military establishment in Islamabad and the administration in Washington. The suspension of Pakistan’s Commonwealth membership, its difficult economic conditions and overall adverse image helped Indian strategist to believe that short lived parity which Pakistan claimed at the eve of a nuclear South Asia in May 1999, has finally been managed – encapsulated within the new perception: nuclear but failed state and thus more dangerous for regional and international order. South Block visionaries that had spent greater part of their energies throughout 1990’s in getting Pakistan declared a “rogue state,” sponsoring terrorism naturally felt comfortable that now finally a multi-dimensional strategic relationship with US can emerge without the troubling shadow of Pakistan, clinging to it.

Indian Strategic Response After 9/11

Indian strategic thinkers were quick to assess the impact of terrorist attacks in New York and – with the Pakistani jump into a willing and needy American lap – its possible effects on the region. Increased political space for Pakistan would mean reduced one for India for two reasons: One, Pakistan will find new diplomatic and media support for the cause in Kashmir and Secondly, US will be under pressure to balance its strategic tilt towards India out of deference for its new relationship with Pakistan. There are indications that before 9/11 Indians were expecting US President Mr. Bush to visit India in the first quarter of 2002. And now Indians could clearly see that with operation in Afghanistan and Pakistan’s support against Taliban, any such visit of the US president will be delayed for at least a year and if and when it will materialize, it will probably be a usual joint visit to both India and Pakistan – something which Indian strategy saw as a serious setback to the gains made during the last years of Clinton presidency.[6]

A day by day follow up of Indian press in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 brings out that tremendous anxiety through which Indian decision making elite, both within and outside the government, suffered at this critical moment. Cabinet Committee on security met on September 13, to lay out the bare bones of a response strategy and this meeting, among others, was attended by the Foreign Secretary, Ms. Chokila Iyer, and the Chief of Air Staff, Air Chief Marshal A.Y. Tipnis. The consensus that emerged was that it is must for India to develop an active identification with US administration’s counter-terrorism drive.[7] By that time, Prime Minister Vajpayee had already written a letter to the US President Mr. George Bush, saying India is “ready to cooperate in the investigations into this crime and to strengthen our partnership in leading international efforts to ensure that terrorism never succeeds again.”[8]

But what will be the contours of that cooperation? There is overwhelming evidence that in the first week following 9/11, Indian political and bureaucratic elite were prepared to go a long way to be part of US led coalition. Given the geographic and thus logistic needs of then potential US operations in Afghanistan, it is somewhat surprising that Indian elite expected to become, in one way or the other, a part of the military operations.[9] On September 15, in a two hour meeting, chaired by the Prime Minister, the opposition, barring the exception of CPI(M), was united on offering base facilities to the US. However, the leaders were informed that there was no formal request from the US for the use of Indian bases to carry out military strikes in the region.[10]

By that time, even the liberal press had openly come out with the argument that India’s ‘strategic card’ is to bank on America’s military might to try and silence the guns of Pakistan-sponsored militancy in Kashmir.[11] It was thus extremely disconcerting to the Indian elite and middle classes when, around this time, they learnt that they were probably not getting an important role in the US led coalition because Pakistan had asked Americans to keep India and Israel out of this effort. In all probability, it was true, however, US officials took exceptional pains to soothe the Indian sensitivities on this issue.[12]

It was around this time that President Bush called Mr. Vajpayee to assure of the importance US administration attached to India’s role in the war against terrorism. However, on September 18, the Indian legislators gave a tough time to PM and External Affairs Minister on the question of Americans pandering to Pakistani sensitivities. And it was second time in less than a week that cabinet was utterly disappointed to learn that the Indian government has not received any formal request of assistance from US. Later, in the evening, the Prime Minister also told reporters that, “no specific requests” for assistance had been made by the US but dismissed as “hypothetical” another question – whether India was prepared to give “all assistance” as and when the American requests came in.[13]

Indian anxiety was by then clearly palpable across the borders by the Pakistanis. On September 19, Gen. Musharraf, in his famous “lay off” speech said, “They have offered all military facilities to America. They want America on their side. The objective is to get Pakistan declared as a terrorist state and harm our strategic interests and the Kashmir cause.” Though, he did not mention who they were but it was obvious, he was referring to India. In India, on the other hand apprehension was mounting as summed up in The Hindu’s editorial of September 18, that “contours of a possible coalition are still far from clear.” And again on September 20, The Hindu pointed out that “regardless of tacit American assurance that present tie-up between the US and Pakistan need not destabilize peace and politics elsewhere on the international stage, the plan of forming the nucleus of a globalised alliance against terrorism does not yet seem to have crystallized.”[14]

However, the best summing up of India’s apprehensions and interests in the changed scenario was offered to Americans by a prominent academic, Kanti Bajpai, of the School of International Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi. His views appeared in an op-ed, published in The Hindu of September 22 and are of such far reaching significance that they deserve a detailed treatment. Kanti argued that “storm clouds are gathering over India-US relations” because Indian middle classes are worried that US, out of its present needs, has struck a kind of deal with Pakistan, reminiscent of 1950s and 1980s and Indian concerns and anxieties are to Americans dispensable and that, “ US has sold India down the Indus.”

Kanti argued that US need to get Pakistan in its “coalition of ‘moderate Islamic influentials’ is understandable” and it may be that benefit of having India in that coalition at this stage are unclear but Washington needs to take a long term view. In the long term, it is the large democratic and developing India that is to US advantage and India due to its conflict with Pakistan over Kashmir “ has a stake in the outcome of US policies in the region. India, therefore, matters in a coalition dedicated to managing terrorism problem.”

He then suggested the remedies; it is important to mention a few of them because they have since then seen the light of the day, though perhaps not without a jolt from the Indian administration. (This will come later). First, US should publicly emphasize that it will not make a deal with Pakistan inimical to India’s interests. In a rather interesting fashion he pointed out that US ignored India in the first few days and Pakistan successfully created the impression that it has a special relationship with US and a new deal is in the offing. In the same vain, he suggested that US should be seen doing something in cooperation with India. It may not be something big or dramatic but it should be visible enough to the Indian middle classes to reassure them.

Second, “Washington must, at least privately, tell New Delhi that it will go beyond the immediate terrorism problem focused on Afghanistan.” Kanti did not agree with the thesis that US efforts in Afghanistan will automatically help India in controlling and bringing normalcy to Kashmir. He, then identified the fronts where US should move to allay India’s concerns.

First of all, it should apply pressures on Pakistan to wind down fundamentalist influences. This means at the very least, redefining the role of Madrassa education in Pakistan. In addition, it means rooting out fundamentalist elements in the armed forces. Finally, and most importantly, in the short to medium term, it implies shutting down the militant groups operating in Kashmir. The Lashkar-e-Taiba, the Jaish-e-Mohammed, and the Hizbul Mujahideen are the three most important outfits. Washington should get Islamabad to act hard and fast against these groups and at least disarm them.

The second front that the US should move on, quietly but firmly, is to bring Kashmiri groups round to participating in Kashmir’s electoral process. Some Kashmiri factions and sections are interested in contesting the polls. But the APHC has not come out publicly in support of the idea. Washington should use its influence with these groups. Pakistan will oppose Kashmiris voting and participating in the elections. Here is where the US can again be helpful beyond just Afghanistan. Mr. Bush said that it would be a long hard campaign against terrorist violence and that it would require the use of punitive as well as positive incentives, that any strategy would have to combine economic, diplomatic, and political instruments in addition to the military. This would be a vital test case of subtle, strong, and extended engagement with the issue of terrorism.

Kanti also warned that over the long run these groups may sequester in Pakistan or Kashmir and:

If these groups intensify their operations in India or do something spectacular like September 11 against Indian targets, there will be fantastic pressure on New Delhi to retaliate massively. This could lead to a confrontation with Pakistan, the likes of which we have not seen, with nuclear weapons not far away.[15]

In hindsight, we now know that ultimately US was forced to take a stock of Indian apprehensions and it ended up asking Pakistan to oblige India on all these demands so neatly illustrated by Kanti on September 22, 2001. This also includes a US position favourable to India on the electoral process in Kashmir. So, can a cynic analyst argue that if US had been persuaded quickly enough then the world would have been spared of the spectre of a possible nuclear melt down in South Asia? Perhaps yes, but then in the third week of September, Americans, though acutely aware of India’s importance to their larger world view, did not appreciate the level of Indian desperation and kept on reassuring Indians at various levels, but could not satisfy them. Can one ask the question, “Something dramatic had to happen for Americans to sit up and take notice of Indian concerns?”

On September 25, Indian National Security Advisor and Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister, Mr. Brajesh Mishra, was in Washington, meeting senior Bush administration officials and law-makers who again assured that India is part of the coalition against terror at many levels and in different ways. However he found US administration obsessed with “get Osama” project and took pains to point out that in spite of all the immediate concerns and objectives, the long-term implications should not be ignored or brushed aside. In particular, Mr. Mishra is said to have drawn attention to the networking of the Al Qaeda as it pertains to the ongoing terrorism in Jammu and Kashmir.[16]

Recording the impressions of his visit and reception, Washington correspondent for Indian paper, The Hindu observed, “To say that India is totally out of the loop in the fight against terrorism is exaggerating things. But at least in the short term, the focus here is quite limited as far as the Bush administration is concerned. Senior officials have made no bones of the fact that the prime attention right now is on Osama bin Laden, his network and training camps.” He also noted, “ Mr. Mishra is here also at a time when there has been a tremendous amount of support and political sympathy for the President of Pakistan, Gen. Pervez Musharraf, for his decision to fully align with the US in targeting the Taliban and Osama bin Laden. The political support to Islamabad aside, Washington, along with international financial institutions are putting together a hefty “goodies bag” as well.”[17]

The last week of September 2001 is very important to this analysis, as things seem to be moving to a point of convergence, perhaps to their logical end. The American Ambassador to India Mr. James Blackwell, in his first press conference in India and first major public gathering since 9/11 sought to dispel the perception that since the terrorist attacks against America two weeks ago, Pakistan had once again become the main focus of US policy in the subcontinent.

Mr. Blackwell said the relationship between India and the US had been “transformed in many practical ways” since September 11. This would have happened in any case but the attacks against the US had “accelerated” the process. He told press that India and the US were now engaged in cooperation “unthinkable even a month ago.” The envoy pointed to the “intensity, frequency and transparency” of exchanges between the two Governments at the diplomatic, intelligence and military levels. However, on the Indian offer of support to the US military operations against Afghanistan, Mr. Blackwell said that Washington had not made any request so far. When the US made up its mind on the military strategy to be adopted, it could come up with specific requests.[18]

A different mood emerged in a parliamentary meeting on September 27 in New Delhi. In a sharp distinction to the earlier sentiments expressed by both the government and opposition benches, government now set at rest speculation on the nature of India’s involvement in the proposed US action in Afghanistan. Addressing the meeting, the Prime Minister, Mr. Vajpayee, made it clear that India had not given any assurance either “directly or indirectly” on the use of its airbases. India’s role was limited to intelligence sharing with the US. “We have given no direct or indirect assurance on making available airbases,” Mr. Vajpayee told the meeting. And while pledging support to the Government, the opposition sounded a note of caution against deviating from the long-standing policy of non-alignment.[19] This change of mood was remarkably different from the one that prevailed in the same house only 12 days ago on September 15, when, with the only exception of CPI (M), virtually all political opinion supported extending air bases to US for its operations in Afghanistan.

In an equally significant change of tone, the Parliamentary Affairs Minister, Mr. Pramod Mahajan, in a press conference immediately after the two hour long parliamentary meeting, said the Government had made it clear that it was not under any illusion and was not depending on anyone in its fight against terrorism.[20] In an apparently unrelated development but nevertheless of significance in hindsight, the newspapers one day earlier, on September 27, carried stories citing unnamed “top security official” that clarified that contrary to earlier reports, militants are not leaving Kashmir but are actually regrouping and are planning major strikes to register their presence on the ground.[21]

Militants Attack Srinagar’s Legislative Assembly

Kanti Bajpai in his above mentioned op-ed had predicted the possibility that militants when flushed out of Afghanistan may sequester in Indian or Pakistani Kashmir and their terrorist activities may force India to react with force against Pakistan. It may be a little ironical that militants struck exactly one week after his prophetic comments. On October 1, an unprecedented militant attack on the Kashmir Assembly left 38 dead and many injured. The Chief Minister, Dr. Farooq Abdullah, and his Ministerial colleagues had, however, left the venue sometime earlier.[22] India immediately pointed out the finger on Jaish-e-Mohammad, a militant outfit based in Pakistan. An anonymous caller first called to take responsibility of the attack but subsequently the organization formally denied any link or responsibility.

The identity of this anonymous caller was not the only intriguing thing about this militant attack. It also happened at a very crucial juncture in the US led war against Taliban. Indian External Affairs Minister Jaswant Singh was in the process of arriving in a Washington, busy in the final stages of mounting an attack on Afghanistan and thus relatively disinterested in an Indian “wish list on Kashmir.” Washington correspondent of an Indian paper observed that his “arrival barely caused a ripple.”[23] A week earlier National Security Adviser could not get undivided attention from the administration. But now, with terrorist bombing of Kashmir assembly, situation had dramatically changed. US administration had to sit up, open its eyes and listen to an injured India; a democratic partner that may not have been of any immediate military or logistic support for war effort but could certainly wreck the game by opening up any kind of front on the western borders of Pakistan in Kashmir.

Citing the attack on the Jammu and Kashmir Assembly, the Prime Minister, Mr. Atal Behari Vajpayee, wrote to the US President, Mr. George Bush, bringing to his attention the need to urgently restrain Pakistan from backing international terrorists in Kashmir. “Incidents of this kind raise questions for our security which, as a democratically elected leader of India, I have to address in our supreme national interest.” Pointing to the urgency of holding back Islamabad, he said, “Pakistan must understand that there is a limit to the patience of the people of India.” In the letter, sent hours after the car bomb attack, Mr. Vajpayee said, “I write this with anguish at the most recent terrorist attack in our State of Jammu and Kashmir… A Pakistan-based terrorist organisation, Jaish-e-Mohammad, has claimed responsibility for the dastardly act and named the Pakistani national, based in Pakistan, as one of the suicide bombers involved.”[24]

Though many in the State Department, confronted by the faceless monster of international terrorism, might have wondered on the nature of terrorists, who not only intervened at a most propitious moment to bolster the Indian cause, but also called to leave their exact names and details but this was not the time for such reflections. Within sub-continent, India was furiously demanding, in a war like language, that Pakistan ban Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad the two organizations it alleged were freely operating from Pakistan and Pakistan controlled Kashmir.[25] And in Washington, an aggrieved and earnest Indian External Affairs Minister, Mr. Jaswant Singh, was breathing on their necks.

The US President, Mr. George Bush, then personally assured India that the US campaign against terrorism is global and not one-dimensional as seen through the prism of Osama bin Laden and the Al-Qaeda terror network. Mr. Bush conveyed this to the visiting External Affairs and Defence Minister, Mr. Jaswant Singh, when Mr. Bush not only dropped in at a White House meeting between Mr. Singh and the US National Security Advisor, Dr. Condoleezza Rice, but spent 45 minutes of a 75-minute discussion with him. Washington correspondent of Indian paper,The Hindu, reported that, “Mr. Bush had good reasons for spending his time at the meeting in spite of his hectic schedule….New Delhi has been quite wary of the growing Washington-Islamabad nexus, especially as it pertains to fighting terrorism.” [26]

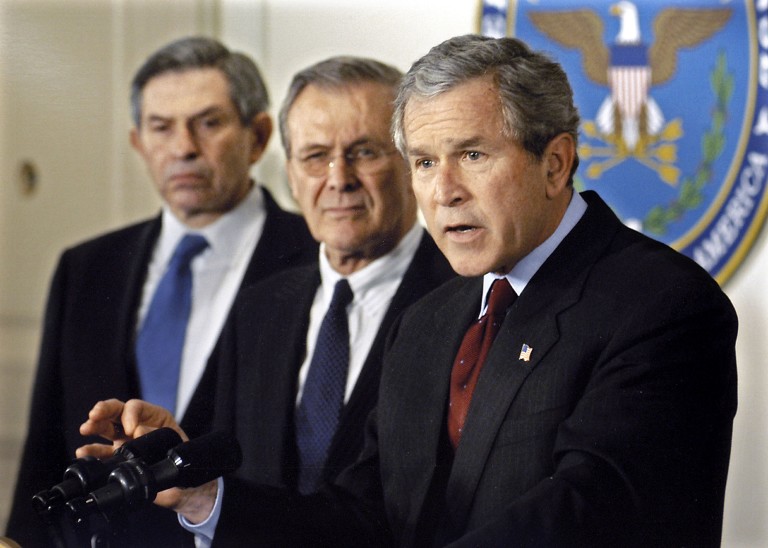

Next day, as Mr. Jaswant Singh stood by the Secretary of State, Mr. Colin Powell declared, “The events that took place in Kashmir yesterday, that terrible terrorist act, that heinous act, that killed innocent civilians and also struck a government facility… It is the kind of terrorism that we are united against.” In a message, Gen. Powell reiterated, “And as the President made it clear… we are going after terrorism in a comprehensive way, not just in the present instance of Al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden, but terrorism as it affects nations around the world, to include the kind of terrorism that affects India.” But Gen. Powell would not comment on any specific allegations that Pakistan was behind the terrorists in Afghanistan or Kashmir.[27] It was certainly music to Indian ears but still inability of the administration to condemn Pakistan for the acts was disappointing. Powell’s caution was also shared by Secretary of Defence, Donald Rumsfeld. It is important to mention here that this was probably the first time that administration openly used the word “Al-Qaeda” in the context of Kashmir. India wanted to hear “Pakistan” instead of “Al-Qaeda,” however, later Indian government and media, often talked of Al-Qaeda and Pakistan as one and the same thing.

This discussion, at this crucial juncture, will remain incomplete if we do not make some brief comments on the “false alarm of hijacking” that took place between the nights of October 3 and October 4. A Boeing 737 of Alliance Airlines, a subsidiary of the Indian Airlines, that took off from Mumbai at night bound for Delhi, was soon declared hijacked by the Civil Aviation authorities. International media treated the news with scepticism raising the question that why India was not more careful in the prevailing circumstances. Pakistan promptly closed its airspace and alleged citing its own intelligence sources of October 2 that this is a plan to implicate Islamabad to intensify the international pressure being created since the Kashmir Assembly bomb attacks.[28]

The plane had landed at Delhi, and crisis management team met under Union Minister L.K. Advani. Plane was surrounded by NSG commandos and media was watching the story for a live coverage. However, by 4am the civil aviation authorities finally declared that hijacking was a “false alarm” and was caused due to confusion inside the cockpit. Unfortunately the sudden happy resolution left many questions unanswered. To begin with, there was a call to the offices of Alliance Airlines informing of the hijack. And at the height of the crisis, the Civil Aviation Secretary, Mr. A.H. Jung informed the press that there are two hijackers on board who do not speak good English. A visibly embarrassed Vajpayee government ordered a high powered inquiry to investigate the origin of this false alarm but only six days later the 24 year old young man who had received the anonymous call, and was, therefore, a crucial witness to this investigation, was found dead of a heart attack.[29]

In the following week, British PM Tony Blair visited sub-continent and Mr. Vajpayee, now unfettered to blame Pakistan in front of international cameras, kept on rubbing in his mantra about Pakistani terrorism. In an obvious reference to Pakistan, Mr. Vajpayee said, “we discussed the sinister agenda behind the Srinagar bomb blast. Even while extending our whole-hearted support to the pursuit of the guilty terrorists of September 11, we should not let countries pursue their own terrorist agenda under cover of this action.”[30]

It is time for us to take stock of the situation. This was second week of October 2001 and by now US Secretary of State, Colin Powell’s visit to the troubled region, i.e. subcontinent, was already announced and US and British bombings to aid Northern Alliance had already begun. Pakistan was too deeply embroiled into this situation and was providing assistance of all sorts to the US led coalition. The main goal of US and British diplomacy – after realizing the extent of Indian desperation – was to placate Indians in such a way that prevents them from creating trouble for their war effort.

Indians, it can be argued, fashioned and waged a successful strategy that helped them to barge their way into a situation by creating nuisance for the US led war effort. Indians knew their importance in the overall US worldview and knew they were taking calculated risks. Though US would not have ignored them in the long term anyway but they were apprehensive, as so clearly illustrated by Kanti Bajpai of JNU, on two major counts: One, Pakistan might develop a sustainable relationship that can put pressure upon them for some sort of dialogue on Kashmir. Second, in relative terms, the new US-Pak relationship may interfere with their already achieved but as yet nascent position in the emerging world order – that to a great extent depends upon Indo-US road map at least at this stage.

In hindsight, we can see that by the end of first week of October, they had successfully completed the first part of their strategy. They caused nuisance and were rewarded for it. And this exercise further helped them to understand and fine tune the pressure they could bring upon Pakistan by threatening to upset the interests of US. By the second week, Pakistan’s President Gen. Musharraf, prodded on by the US and Britain, was talking to Vajpayee assuring him of conducting an inquiry into the whole matter. When Musharraf expressed his desire that the stalled process of dialogue between India and Pakistan should be reinitiated, Vajpayee reminded him that if Pakistani focus would remain on Kashmir then no progress would be made. A patient Musharraf, aware of the fast changing kaleidoscope, politely listened.[31]

In Washington on October 11, Gen. Powell, when asked by CBS-TV whether the US was concerned that India might try to take advantage of the situation and ignite a conflict while the world is distracted, answered, “I don’t think that will be the case. In fact, we have been in touch with both governments and they both realize the volatile nature of this situation and I think both of them understand this is not the time for provocative action, which would cause the situation in the region to become unstable.” He further said, “both countries had been very forthcoming in terms of the support in the US-led campaign against terrorism. Pakistan is on the front lines of it, really, because of their proximity to Afghanistan, and President Musharraf has done quite a number of very important things. The Indians have also been very forthcoming with the support that they have given.”[32] Perhaps what he meant was that Indians are helping by not opening another front in the west of Pakistan, in Kashmir.

In his subsequent visit to Pakistan and India, Powell was treading a careful path. He assured Pakistanis that US takes a long term view on the region and will thus maintain its engagement with Pakistan beyond Afghanistan. In his press conference in Islamabad, he described Kashmir as central to Indo-Pakistan relations and encouraged dialogue between the two countries. “We believe a dialogue on Kashmir is important. We believe maintenance of the Line of Control and the exercise of restraint is also very very important and avoidance of provocative acts which could lead to a conflict of any kind,” he said.[33] However, during his follow up trip to India, Ministry of External Affairs promptly rejected that Kashmir is central to the conflict between India and Pakistan and further clarified that India wishes to address Indo-Pak relations only in a “composite manner.” [34]

Militant Attack on Indian Parliament

Though the coercive diplomacy that India set into motion after the “mysterious attacks” on the Indian Parliament on December 13, remained the focus of intense press commentaries but it would only be fair to argue that Indian strategy had developed its basic skeleton, and won a tacit US approval for itself. By the middle of October and the six-month long duel that started two months later was only to accentuate and consolidate its dominant position. Pakistan no doubt, along with US, was at the receiving end of this campaign, but it could also be seen as a clear Indian declaration of “regional assertion” to the world at large. Strategists in south block understand too well the importance of war fought on media to the emerging global consciousness.

The timing of the attack on Indian Parliament is worth examining. The Srinagar bomb blasts took place on October 1, at the very beginning of the US led campaign in Afghanistan. By that time Northern Alliance struggle was well on its way and direct US air attacks were imminent. As we have seen the terrorist attacks in Srinagar brought India, which had hitherto felt ignored, into the centre of the things. From the second week of October onwards, when US and Britain understood Indian dilemma and made public and private efforts to assuage the Indian fears, nothing of any significance, whatsoever, happened in India or Indian controlled Kashmir till the very conclusion of the war in Afghanistan. This was the time when an operation of somewhat unpredictable duration was undertaken in Afghanistan to which Pakistan provided a crucial launching pad. We can safely surmise that US would not have looked kindly on any distraction at this juncture – especially one with doubtful credibility.

Kabul had fallen on November 13,[35] however, the struggle continued till Taliban surrendered Kandhar on December 8.[36] Hamid Karazai, the head of interim government, arrived in Kabul on October 10, and the struggle against remnants of Taliban was limited to Tora Bora caves. The US administration and media could now conceivably be persuaded to look on issues elsewhere. It was precisely at this time, and not before, that the unknown terrorists decided to attack Indian Parliament buildings in New Delhi on December 13. In terms of timing, terrorists provided a most propitious moment for the Indian government to draw world attention to their concerns regarding Kashmir. Could it be argued that things inside India have faithfully followed a decent and responsible timetable? After all everyone from London to Brussels to Washington was telling New Delhi, from September onwards, that its concerns about Pakistan sponsored terrorism in Kashmir are genuine and will be addressed at an appropriate time. What could have been more appropriate time than the end of war in Afghanistan?

India quickly claimed that “dead attackers” of the Indian Parliament were of Pakistani origin; it arrested their accomplices, and found out Pakistani markings on weapons employed. However, it refused showing the faces of the dead men to the press, twice refused Pakistani requests for a joint inquiry and turned down FBI offers for investigations into the crime. Pakistanis condemned the attacks, offered their help and cried “conspiracy” but their arguments, however, reasoned they might have been, were of little consequence. By December 20, Indian strike forces were on move towards the borders.

India recalled its ambassador from Pakistan and terminated its land and road links. It was the first time since 1971 that India took the step of recalling its envoy back from Pakistan. Under tremendous pressure from US and Britain, and less pronounced sources from EU, Pakistan moved in steps and stages to arrest leaders of militant outfits operating in Kashmir and banned their organizations. US took the lead by branding Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations” and Pakistan followed the suit. Gen. Musharraf in a much awaited televised address to the nation on January 12, announced his decision to ban these militant organizations and invited Vajpayee for talks.

Elections in Indian Controlled Kashmir

Pakistani government’s decision to ban these militant organizations was less of a physical consequence as they were not reliant on government support and hardly maintained bank accounts in their names. Also there is reasonable evidence to suggest that by end 1990s, militancy, barring the sudden inexplicable dramatic events that were helpful to Indian public relations strategy, had ceased to be of any serious consequence to Indian hold in Kashmir. However, Pakistani decisions under US pressure and India’s coercive diplomacy were helpful to India as they sent powerful signals to change the overall context of the Kashmir struggle. It graduated ingloriously from a people’s struggle into a foreign sponsored terrorism against a legitimate government. Kashmiris, pitched against a regional hegemon of the size and power of India, relied upon Pakistani support of sorts to balance the odds. Even the nationalists like Sheikh Abdullah and his followers, that have sought to find, at various stages, an autonomous expression in alliance with the Indian Union have relied upon ‘Pakistani threat’ to further their agenda of extracting political concessions from Delhi.

Pakistani presence on their borders and its vocal support, then ensures a dream pipe of sorts for Kashmiris of all political opinion; it inspires disenfranchised poor masses with the romantic possibility of freedom, however distinct it may be; it offers moderate political forces, who realize the staying power of Indian Union, better chances of clinching a dialogue with Delhi and ironically it has helped a generation of non-entities like Bakshi Ghulam Muhammad and Farooq Abdullah to sustain a political profile by blackmailing a Delhi – afraid of Kashmiri masses’ romantic attachment with Pakistan.

The spectre of a Pakistan locked in a nut cracker, and being pushed to a corner under India’s coercive diplomacy, perceived as being aided and abetted by a conniving Washington, sent the message to Kashmiris which India so desperately wanted to send; a besieged Pakistan can’t come to their aid. Indian strategy has to talk of ‘Pakistan sponsored terrorism’ as it is a marketable commodity to western audience but in reality it needed to clip that Kashmiri ‘pipe line of hope’ that ‘Pakistan stands at the border.’ Indian strategists correctly concluded that with this ‘hope pipe line’ gone, Kashmiri political elements, across-the-board would clearly see the reality fate has prepared for them.

With the hindsight of the events that have unfolded, it can safely be argued that it was certainly a great victory for the Indian strategy as it set the stage for an election exercise that was given US and EU blessing from the beginning. International media also extended its good will, and APHC was under pressure to remain at least ambivalent, if it could not extend its support. Whether India is prepared or even capable of producing a political formula that can satisfy the aspirations of Kashmiri people, with or without the framework of Indian Union, is a different discussion, beyond the scope of this paper. However, one thing is getting clear that with this success of Indian strategy on the horns of a carefully crafted coercive diplomacy, Indian need, desire and even ability to enter into a meaningful dialogue with either Pakistan or Kashmiris has further declined.

Emerging Imperatives for US Policy

In order to better understand what attitudes US policy makers now take towards Kashmir, we need to appreciate the dynamics that govern Indo-US road map and how they are essentially different from those with Pakistan. US imperative to build a closer relationship with India stems from three closely related but yet distinct factors. One, after the end of Cold War, and with the appreciation of China as a strategic competitor rather than partner, it increasingly sees India as a counterweight to China. Second, with the liberalization of Indian economy, U.S corporations see Indian corporate world as a partner and India as a large potential market. Third, Americans of Indian origin are now emerging as a potent force that has started to influence domestic US politics in myriad ways.

These imperatives in themselves are not new. India always enjoyed serious consideration in US strategic view of the region and the world. Even in the Cold War days when India either strongly criticized US policies as leader of the non-aligned movement or later as a pro-Soviet state, US remained conscious of India’s importance and thus careful in handling India. And even otherwise, India had powerful voices inside US academic world and liberal circles that could instil some balance in its favour. Kissinger comments in his latest book: “Indian leaders….calculated correctly that, based on its democratic institutions and elevated rhetoric, it had enough friends in liberal and intellectual circles within United States to keep American irritation within tolerable bounds.”[37]

However with the end of Cold War and India’s need to grow out of the Russian camp, and its opening of economy to foreign companies, the various imperatives driving US policy have finally converged to provide a sort of road map for Indo-US relations. On the contrary, US relations with Pakistan, from the very beginning, developed within a limited bandwidth of government to government interaction. Pakistan never had any friends in academic or liberal circles that shape public opinion and policy within America. US administrations, one after the other, have looked upon Pakistan as a convenient policy tool; may be trusted and loyal but essentially disposable. Though this certainly cannot explain the ups and downs of Pak-US relations in entirety but can help to understand the unstable dynamics that govern it.

Another related factor, but of distinct importance on its own, needs to be understood. Though US after the Gulf War gradually emerged as a kind of de-facto global government and certain scholars have argued that with its control of multilateral institutions and media, it is in fact a new kind of Empire,[38] the exercise of power and influence within the American society is if any thing very different from past empires. Much of public debate and policy formation, critical to foreign relations, at the level of Senate and Congress takes place in a context that is highly influenced by a topical consciousness inspired by media.[39]

Pakistan suffers from natural disadvantages in this kind of exercise. It had few friends – if any at all – within the popular media that shapes American consciousness and in turn policy making. Most of its support historically has originated from the old “realist” school of thought or from government agencies like Pentagon or CIA or those former US diplomats that have served in the region and have, therefore, a first hand intimate understanding of issues that confront US policy and affect US long term interests. Such a small pocket of support would have mattered something in an old style British or Soviet empire, where matters of national interests, even at the periphery, were influenced by a coterie of informed opinion. But in a rapidly fluctuating sea of topical public opinion, influenced by powerful lobbies and in turn bearing upon policy decisions, this limited pocket of support amounts to little more than ‘nothing.’

In the aftermath of Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, two factors then easily altered inherently unstable Pak-US relations. One, in wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall and emergence of East Europe from under the iron curtain, there was a sudden loss of interest of US policy makers and thus administration into this region in the north of India. Second, the struggle in Afghanistan also influenced the polity within Pakistan, and a society and administration emerged, that was more closely identified with causes in the Middle East. This shift towards the right of religious spectrum in itself would have mattered little if US, in yet another short sighted policy reversal, had not imposed sanctions on Pakistan under the Pressler Amendment. These sanctions failed to achieve their stated objectives, however, they reduced good will for US in both Pakistani public and government.[40] The net effect was a reduced influence for US in this region as a whole and a streak of ‘Anti Americanism’ never seen before.

It is essentially within this context that US policy towards Pakistan and Kashmir needs to be understood. Indo-US roadmap towards a strategic relationship of wider significance is not necessarily a threat to Pakistan, if both sides take a mature attitude. For Pakistan, it is important to appreciate the combination of imperatives driving US policy and for Americans it is important to prevent it becoming a “zero sum game.” During the phase of Indian coercive diplomacy, US policy makers have repeatedly tried to assure Indians that a Pak-US and Indo-US relation should not be looked upon as a “zero sum game.” That was when a belligerent India was threatening to disrupt US interests. The test of US maturity now lies in how it will interact with a Pakistan in which religious parties in the shape of MMA have swept western and north-western belts of Pakistan on a mix of aggrieved Pushtun sentiments and Anti-Americanism. And as a consequence, Kashmir also remains a defining issue for large sections of Pakistani populace.

Given the strong imperatives inherent in Indo-US roadmap and the increasing influence of Indian lobby inside US, it is widely feared that US will pressurize Pakistan to accept LOC in Kashmir as a solution; in other words subscribing to the Indian position that Kashmir is an internal issue. The underlying assumption of US policy, as exhibited so far, is that one-sided pressure can be endlessly applied to Pakistani state to nudge it in a desired direction with some economic incentives on the way. This is a dangerous assumption because if this policy continued, it will radicalise Pakistani politics, strengthen the anti-American feelings and threaten the stability of Pakistani state and society by sharpening the wedge between the governing elite and the governed. Formation of non-state actors will then jeopardize US interests in a vital region where it has – despite a deep sense of betrayal – to this day enjoyed tremendous institutional good will.

What possible solution can emerge in Kashmir acceptable to both India and Pakistan is beyond the scope of this paper but to develop a road map towards it, and to prevent regional stress waves, US needs to persuade both states for a dialogue. And it needs to develop a comprehensive relationship with Pakistani state and society at various levels. This relationship needs to grow out of the much-repeated aphorism of Pakistan being “our frontline partner against terrorism” to a platform where Pakistan is perceived as a moderate Muslim country with strong institutional and public links with US. The best guarantee for that to happen is if Pakistan can develop cultural and business exchanges with US and can make it attractive for US investments. Though US administration cannot certainly persuade corporate America to take an interest in Pakistan, but it can help Pakistan improve its business climate to make itself more attractive. A number of steps are badly needed.

One, US should help improve Pakistan’s judicial and court system by helping to develop a comprehensive blue print and providing funds and technical support. Though, Pak-US cooperation to improve law and order situation is emphasized in a narrow sense but it needs to be understood that no lasting solution to this problem can emerge if court procedure and performance is not improved. An assertive and self respecting judiciary that can uphold the spirit of law in a transparent fashion can provide the basis for a mature and realistic relationship for Pak-US relations. The US administration’s decision not to bully Pakistan for the extradition of Omar Saeed Sheikh[41] was a mature decision[42] and in the same vein it may be said that the whisking away of Mir Aimal Kasi in 1998, without the transparent ‘due process of law’ was damaging to the judicial institution within Pakistan.[43]

An independent and strong judicial system will contribute in two distinct yet interrelated ways. It will help improve the law and order situation and it can instil business confidence by strengthening the exercise of contract law and increasing the predictability of business transactions. The row over the Independent Power Producers (IPP’s) in late nineties severely damaged the investment climate and confidence needs to be restored if Pakistan has to attract US corporate interest.

Second, with the revival of democracy in Pakistan, US should now move forward to develop a multi-level relationship with Pakistani parliament. The best strategy for Pakistani parliament to acquire greater authority vis-�-vis military and civil bureaucracy will be by consolidating parliamentary procedure and US can provide valuable help to strengthen the committee proceedings. Third, the limited academic exchanges between US and Pakistani think tanks, universities and media need to be expanded. And this should include the programs for US scholars to visit and stay within Pakistani institutions.[44] This can help create a better understanding of respective positions. It needs to be understood that anti-Americanism in Pakistan did not start from bottom upwards but has travelled down from the elite in government and media that felt betrayed by the American attitudes and sudden reversals of policy e.g. Pressler Amendment.

Finally re-establishing the long abandoned training exchanges between US and Pakistani militaries and joint exercises will go a long way in assuring Pakistanis that far from being sacrificed in a “zero sum game” they are part of US strategic vision for this region. Best hope for a Kashmir solution – satisfactory to both India and Pakistan – now also lies embedded in this kind of arrangement.

* Dr. Moeed Pirzada, a Kashmiri of Srinagar origin, studied International Affairs at Columbia University, New York and is currently a Britannia Chevening Scholar at London School of Economics and Political Science.

[1] Sundeep Dikshit, “Strike forces moved closer to the border,” The Hindu, December 21, 2001. The movement involved troops from central India, along with tanks and bridging equipment as well as other armoured units towards the International Border with Pakistan along Rajasthan and Gujarat. The increase in military traffic to the western border was apparently, according to Indians, in response to Pakistan’s deployment of its strike forces – Army Reserves (South) and Army Reserves (North); Pakistan saw it differently. It is, however, important to realize the speed with which forward deployment started to build up.

[2] This scenario was first raised by Dr. K. Subrahmanyam, a leading Indian strategic thinker (and principal author of the 1999 Draft Nuclear Doctrine) in an oral presentation at the University of California at Berkeley on October 8, 2001. Dr. Subrahmanyam argued that in a future coup, Pakistani’s nuclear assets can fall in the hands of religious fanatics and made it abundantly clear that New Delhi would expect the US to take out Pakistan’s bomb in that case. Since then, it has been used much more loosely in Indian and Pakistani press and discussed on US media.

[3] Muthida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA), a combined electoral alliance of religious parties that swept Pakistan’s north-western and western provinces in the 2002 elections on a campaign of anti-Americanism predicated on aggrieved Pushtun sentiments due to American bombings on Afghanistan.

[4] See, for instance, detailed discussion of the US perceptions, interests and attitudes towards both India and Pakistan by Bruce Riedel in his paper “American Diplomacy and the 1999 Kargil Summit at Blair House” submitted in Policy Paper Series 2002 at The Centre for the Advanced Study of India, University of Pennsylvania. Riedel was special Assistant to the President and senior Director for Near East and South Asia Affairs in the National Security Council at the White House from 1997 to 2001.

<http://www.sas.upenn.edu/casi/reports/RiedelPaper051302.htm>.

[5] Ibid. A careful reading of Bruce Riedel’s account in the above cited policy paper will clearly illustrate the point. This was also a common perception in Pakistani press and quoted in other places, for instance, see Tariq Ali, Clash of Fundamentalisms. In chapter 16th of this book, “Plain Tales from Pakistan” he writes, “Yes, it was another coup, but with a difference. This was the first time the army had seized power without the approval of Washington. In October 1999, Nawaz Sharif, with US support, attempted to remove General Musharraf as Chief of Army Staff of Pakistan Army. They chose to do so while he was in Sri Lanka on an official trip. The plan backfired.” Tariq Ali, Clash of Fundamentalisms (London: Verso, 2000), p. 200. These comments are important as Tariq Ali, a die hard Marxist, has been a fierce critic of Pakistani military and in his controversial book, Can Pakistan Survive?, he severely criticized Pakistan military.

[6] Chidand Rajghatta, “Jaswant to hard sell India in US,” The Hindu, October 1, 2001.

[7] Atul Aneja, “Government discusses fall out of the US attacks on the region,” The Hindu, September 14, 2001.

[8] The Hindu, September 13, 2001.

[9] Atul Aneja, “US may turn to India if Pakistan refuses air bases,” The Hindu, September 16, 2001. This detailed news report makes an interesting reading in the sense that Indian elite at that time seems to be making lot of emotional investment into the issue of bases to US.

[10] The Hindu, September 16, 2001. “Proceed with caution,” report by Special Correspondent. In this meeting the CPI (M) said, in a written statement, that it strongly opposed the Government’s move to offer logistical facilities and participate in the proposed US military action. “We have reiterated this position clearly again in the meeting.” This was the only note of dissent from the whole political spectrum.

[11] See for instance editorial of The Hindu, September 16, 2001, “Seeking an active role,” in which the most liberal of the Indian papers argued that India has to be clear and specific about its objectives in siding with the US led coalition.

[12] The Hindu, September 19, 2001, “Reports of Pak. Conditions false,” by special correspondent. US Ambassador to India, James Blackwell had to personally convey these assurances to Union Minister Mr. L. K. Advani.

[13] Harish Khare, “Fears over US-Pak. Deal allayed,” The Hindu, September 19, 2001. It is also helpful to read The Hindu’s editorial of September 19, “An evolving anti-terror agenda.” This discussion, like many others, help to understand the deep-seated anxiety that had started to grip the Indian mind on the issue of being left out from the US led campaign.

[14] The Hindu, September 18, 2001. Editorial, “An evolving anti-terror agenda,” and also see editorial of September 20, 2001, “Towards an Anti-terror Alliance.”

[15] Kanti Bajpai, “India-US ties after September 11,” The Hindu, September 22, 2001.

[16] Sridhar Krishnaswami, “Mishra makes his point on terrorism in J & K,” The Hindu, October 26, 2001.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Raja C. Mohan, “Unprecedented Cooperation,” The Hindu, September 27, 2001.

[19] “No promises to U.S: PM, ” The Hindu, September 28, 2001.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Shujaat Bukhari,“Militants not quitting the Valley,” The Hindu, October 27, 2001.

[22] Shujaat Bukhari, “ Suicide bomber targets J & K Assembly,” The Hindu, October 2, 2001.

[23] Rajghatta, Chidand, “Jaswant to hard sell India in US,” The Hindu, October 1, 2001.

[24] Atul Aneja, “ It is time to restrain Pak. PM tells Bush,” The Hindu, October 3, 2001

[25] “Rein in Lashkar, Jaish too, India tells Pak.,” The Hindu, October 2, 2001.

[26] Sridhar Krishnaswami, “Campaign Global: Bush,” The Hindu, October 3, 2001.

[27] Sridhar Krishnaswami, “ J & K too on agenda: Powell,” The Hindu, October 4, 2001.

[28] Bhaduri Nilanjan Jha, “The Hijack that never was” Times of India, October 4, 2001. For step by step details see “ A blow by blow Account” in Times of India of October 4 and details regarding the Pakistani assertions see “ Hijack Drama aimed at Discrediting us: Pak.,” Times of India, October 4, 2001. A good account is also available in “Alliance Air Plane Hijacked,” by Harish Khare in The Hindu of October 4, 2001.

[29] Ambreen Ali Shah, “Sudden death of a witness in Hijack Drama,” The Telegraph (Calcutta), October 10, 2001. The witness, Shahnawaz Wani, was the supervisor on duty in the Alliance Airlines office in Delhi, who received the anonymous call informing that the plane was hijacked and he had then set into motion the security operation by informing his superiors. With his death, this lead was finished right at its origin.

[30] “Check Countries sponsoring Terrorism; says Vajpayee,” The Hindu, October 7, 2001.

[31] Harish Khare, “Musharraf rings up Vajpayee,” The Hindu, October 9, 2001.

[32] “India won’t ignite the conflict,” The Hindu, October 12, 2001.

[33] “Resume Dialogue,” The Hindu, October 16, 2001.

[34] “India raises Powell’s remarks on Kashmir,” The Hindu, October 17, 2001.

[35] “Northern Alliance Forces enter Kabul,” The Hindu, November 14, 2001.

[36] “Taliban Surrender Kandhar,” The Hindu, December 8, 2001.

[37] Henry Kissinger, Does America Need a Foreign Policy? (New York: Simon & Schuster), p. 156.

[38] The best assertion of this view comes from Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s book, Empire, in which they argue that today’s empire draws on elements of US constitutionalism, with its tradition of hybrid identities and expanding frontiers.

[39] Stephen Walt, Professor of International Affairs at Harvard University’s John. F. Kennedy School of Govt., pointed out in a far reaching article in Foreign Affairs that, “two thirds of the Republicans elected to Congress in 1994 reportedly did not possess passports and argued that due to decline of interest in foreign affairs the power of special interest groups who take strong focused positions has increased. For a detailed discussion see: Stephen Walt, “Two Cheers for Clinton’s Foreign Policy,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2000 (Vol. 79, No.2), pp. 65-66.

[40] The White House Press Briefing on April 11, 1995, immediately after Bhutto-Clinton meeting gives a fairly good idea that State Dept. did realize the negative fallout of Pressler Amendment and its implications for US interests in this region but remained stalled due to the complexity of legislative process. A question arises: The complexity of US procedures may be of relevance to academicians but does it help the people of Pakistan who see repeated US betrayals? Transcript of this briefing is available at

< http://www.fas.org/news/pakistan/1995/950412-387114.htm>

[41] Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh was awarded death penalty by a Pakistani court on July 15, 2002 in the trial related to the abduction and murder of the Wall Street Journalreporter Daniel Pearl. Dawn, July 16, 2002.

[42] For details see, “Agreement on Omar’s trial in Pakistan,” Dawn, May 12, 2002. After Pakistan’s Interior Minister, Moinuddin Haider visited US in May, it was announced by States Dept. that Pakistani judicial system should go first. It was still not clear if US will like to try him later or will the trial in Pakistan will be considered sufficient.

[43] Mir Aimal Kasi, a Pakistani citizen was convicted by a Virginia court of the murder of two CIA employees outside Agency’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia on January 25, 1993. On June 15, 1997, Kasi was arrested in a remote tribal area inside Pakistan and was flown out of Pakistan without any due process of extradition. It was claimed that his extradition took place under the 1931 treaty concluded between the British Empire and US. However, later his lawyers, provided by the Virginia State, pointed out that his extradition was illegal, as the 1931 treaty did not apply to his case as it stipulated that extradition has to take place in accordance with the law of the land from which prosecution seeks to extradite the defendant. However, in reply, the Supreme Courts of Virginia and US maintained that Kasi was not extradited but was instead ‘kidnapped’ by the FBI and as such there was no violation of the treaty. Kasi was later executed by lethal injection on November 14, 2002. For details, see “Aimal Kasi to be executed on 14th,” Dawn, November 6, 2002.

[44] This is important because Pakistanis travelling and living in US are common and Pakistani scholars tend to understand US position much better than their American counterparts. Programmes similar to that, usually offered in India, which makes it possible for US scholars to live with universities and think tanks, should be created.