Moeed Pirzada | FB Post |

From “The Taliban Shuffle”by Kim Barker (published by Doubleday):

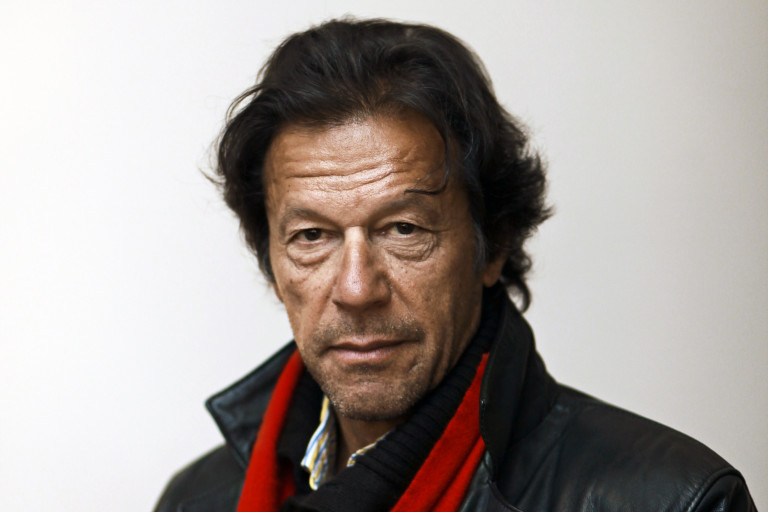

“With Bhutto gone,I needed to meet the lion of Punjab,or maybe the tiger. No one seemed to know which feline Nawaz Sharif was nicknamed after. Some fans rode around with stuffed toy lions strapped to their cars. Others talked about the tiger of Punjab. By default,Sharif,a former prime minister like Bhutto,had become the most popular opposition leader in the country. He was already the most powerful politician in Punjab,which was the most powerful of Pakistan’s four provinces,home to most of the army leaders and past rulers. Some people described Sharif as the Homer Simpson of Pakistan. Others considered him a right-wing wing nut. Still others figured he could save the country. Sharif was once considered an invention of the establishment,a protégé of the former military dictator in Pakistan,General Zia,but like all politicians here,he had become a creature of himself. During his second term,Sharif built my favorite road in Pakistan,a hundred and seventy miles of paved,multilaned bliss…..……

“One of Sharif’s friends tried to explain him to me:“He might be tilting a little to the right,but he’s not an extremist. Extremists don’t go do hair implants. He also loves singing.” I had attempted to see Sharif when he first tried to return to Pakistan a few months earlier,in September. But commandos had stormed his plane shortly after it landed. Within five hours,he had been shipped back to Saudi Arabia,looking bewildered. Sharif had finally flown home in late November,weeks after Musharraf declared an emergency. Samad had driven me to the airport in the eastern city of Lahore,Sharif’s home territory and the capital of Punjab Province. Tens of thousands of supporters waited behind fences across from the airport entrance. Some shouted for the lion of Punjab—others waved stuffed toy tigers or tiny cardboard Sharif cutouts.

It was a classic botched media event. Reporters were herded into a tiny area in front of the airport,surrounded by barriers covered in barbed wire. Thousands of supporters eventually broke through the fences,screaming and running toward us. More and more people pushed into the journalists’ pen,squeezing everyone and driving us toward certain impalement on the barbed wire. Samad guarded a shorter friend of mine. My translator tried to protect my back. I stood in a basketball stance,an immovable force. But not for long. A Pakistani journalist from Aaj TV pushed past me,elbowed me in the ribs,and shoved me to the side. I pushed back. “You don’t see me standing here?” I said. He shrugged. “Women should not be here anyway. This is a man’s job.” The crowd swayed back and forth,and I tried to keep my balance. A man grabbed my butt,a message to my fist,and before my brain knew it,I managed to punch him in the face. Not professional,not at all,but still somewhat gratifying.

That was the chaos just before Nawaz Sharif and his brother walked out of the airport,with me worried about my rear,my position,the barbed wire,a mob,and a potential bomb. Supporters lifted the Sharifs onto their shoulders and spun them around in circles because they had no room to walk. Nawaz Sharif looked shell-shocked. He somehow clambered onto a rickety wooden table next to a taxi stand. The contrast with Bhutto was obvious—she was smooth,a master performer,charisma personified,always in control. Sharif seemed more like a baffled everyman,nondescript and beige. The crush of men waved their arms in the air and shouted that they loved Sharif. He spoke into a microphone,but it was broken and no one could hear anything he said.

Speech over,Sharif climbed down from the counter and slipped into a bulletproof black Mercedes,courtesy of his good friend,King Abdullah,who had also shipped Sharif back to Pakistan in a Saudi royal plane. Now,six weeks later,it was January 2008. Bhutto was dead and Sharif was the only living senior politician in Pakistan. He had been banned from running in the upcoming parliamentary elections because Musharraf still hated him so much—but he would be a major factor in those elections. Sharif was trying to appear like a figure of reconciliation,above all the politics. He publicly cried after Bhutto’s death,and talked about how she had called him for his fifty-eighth birthday,two days before she was killed. I called everyone I knew to try to get an interview.

“You only get fifteen minutes with Mian Sahib,” Sharif’s press aide finally told me,referring to Sharif by his honorary title. “Maybe twenty at the most.” I flew into Lahore on a Friday morning,and we drove for an hour toward the town of Raiwind and Sharif’s palatial home and palatial grounds. The closer we got,the more Sharif. The place may as well have been called Nawaz Land,given the amusement-park feel and the fact that his name and picture were on everything,from the hospital to giant billboards. Everywhere I looked,Sharif—amiable,slightly pudgy,topped with hair plugs—stared at me like the Cheshire cat. Guards checked me at the gate,searching my bag meticulously. The grounds of Raiwind resembled a cross between a golf course and a zoo,with several football fields of manicured grass and wild animals in cages,leading up to a miniature palace that looked slightly like a wedding cake,with different layers and trim that resembled frosting. The driveway was big enough for a limousine to execute a U-turn. I walked inside and was told to wait.

The inside of the house appeared to have been designed by Saudi Arabia—a hodge-podge of crystal chandeliers,silk curtains,gold accents,marble. A verse of the Holy Quran and a carpet with the ninety-nine names of God hung on the walls of Sharif’s receiving room,along with photographs of Sharif with King Abdullah and slain former Lebanese prime minister Rafik Hariri. Finally I was summoned. “Kim,” Sharif’s media handler said,gesturing toward the ground. “Come.” I hopped up and walked toward the living room,past two raggedy stuffed lions with rose petals near their feet. So maybe Sharif was the lion of Punjab. Inside the room,Sharif stood up,wearing a finely pressed salwar kameez,a navy vest,and a natty scarf. He shook my hand and offered me a seat in an ornate chair. The sitting room was a study in pink,rose,and gold,with golden curlicues on various lighting fixtures and couches,and crystal vases everywhere. Many of the knickknacks were gifts from world leaders. His press aide tapped his watch,looked at me,and raised his eyebrows.

I got the message and proceeded with my questions,as fast as I could. But it soon became clear that this would be unlike any interview I had ever done. “You’re the only senior opposition leader left in Pakistan. How are you going to stay safe while campaigning?” In Pakistan,campaigns were not run through TV,and pressing the flesh was a job requirement. Candidates won over voters by holding rallies of tens and hundreds of thousands of people. Even though Sharif was not personally running,his appearance would help win votes for anyone in his party. Sharif looked at me,sighed,and shook his head. “I don’t know. It’s a good question. What do you think,Kim?” “I don’t know. I’m not the former prime minister of Pakistan. So what will you do?” “Really,I don’t know. What do you think?” This put me in an awkward position—giving security advice to Nawaz Sharif.

“Well,it’s got to be really difficult. You have these elections coming up. You can’t just sit here at home.” “What should I do?” he asked. “I can’t run a campaign sitting in my house,on the television.” I had to find a way to turn this back on him. “It’s interesting,” I said. “You keep asking me questions about what I think. And it seems like you do that a lot—ask other people questions. It seems like you’re also willing to change your mind,if circumstances change.” “I do take people’s advice,” he said. “I believe in consultation.” After twenty minutes,Sharif’s aide started twitching. I fired off my questions about Musharraf,the man Sharif had named army chief,only to be overthrown by him. “I do not actually want to say much about Musharraf. He must step down and allow democracy. He is so impulsive,so erratic.”

“Come on. You named this man army chief,then tried to fire him,then he overthrew you and sent you into exile,and now you’re back. What do you think about him?” Sharif nodded,then tried to duck the question. “Appointing Mr. Musharraf as chief of army staff—that’s my biggest mistake.” I stood up. Sharif’s aide was already standing. “I should probably be going,” I said. “Thanks very much for your time.” “Yes,Mian Sahib’s schedule is very busy,” Sharif’s handler agreed. “It’s all right,” Sharif said. “She can ask a few more questions.” I sat down. I had whipped through most of my important questions,so I recycled them.

I asked him whether he was a fundamentalist. Sharif dismissed the idea,largely by pointing to his friendship with the Clintons. I tried to leave again,fearing I was overstaying my welcome. But Sharif said I could ask more questions. “One more,” I said,wary of Sharif’s aide. Then I asked the question that was really on my mind. “Which are you—the lion or the tiger?” Sharif didn’t even blink. “I am the tiger,” he said. “But why do some people call you the lion?” “I do not know. I am the tiger.” “But why do you have two stuffed lions?” “They were a gift. I like them.”……

“Once home from Thailand,I picked up my Pakistan cell phone from my colleague,who had borrowed it. “So,you got a few phone calls,” she said. “One interesting one.” “Who?” “Nawaz Sharif,” she said. I had almost forgotten about the story—I had mentioned his hair plugs,twice,and said Sharif’s genial personality made him seem more like a house cat than a tiger or lion. Ouch. “Oh. Him. What did he say?” I asked. “He wanted to talk to you. I said you were on vacation,and he told me to tell you that you wrote a very nice story,and he liked it. “Really?” Well,that was good news,and meant Sharif was remarkably down to earth. Clearly he had a sense of humor. Bhutto had certainly never called after any story I wrote. I soon called Sharif,to see if I could campaign with him. “You’re the most dangerous man in Pakistan,the top living opposition leader,” I told him.

“I want to see what it’s like to be around you.” “Welcome anytime,Kim,” he said. In mid-February,I met Sharif at the government’s Frontier House,just outside the judges’ enclave,where the country’s former top justices were still under house arrest. Eventually,after slipping through the mob,I climbed into Sharif’s bulletproof black SUV,surrounded by similar SUVs,and we took off,heading for two speeches outside the capital. We left Islamabad. One of Sharif’s security officers somehow sent us down narrow,bumpy dirt roads,where we ended up in traffic jams. Not encouraging. “That was bad planning,” Sharif muttered. He sat in the front passenger seat. I sat behind the driver,next to Sharif’s aide. After various detours,we ended up at the dirt field where Sharif would speak. Thousands of people waited. He was mobbed when he tried to step out of his vehicle,and his bodyguards bounced around like pinballs,trying to get in between well-wishers and their charge. I stood near the dusty stage,but I didn’t want to walk out. Despite Bhutto’s killing,the security at this event resembled that of a high-school pep rally.

The podium didn’t even have a bulletproof glass screen,which was supposed to be there. “I don’t know where it is,” Sharif told me,shrugging. “Sometimes the police give it to me,sometimes they give it to someone else.” Onstage he didn’t seem to care about potential attacks,thundering against dictatorship to the crowd. But I did. This country made me feel insecure,much more than Afghanistan. We drove to the next rally. I looked at my BlackBerry and spotted one very interesting e-mail—a Human Rights Watch report,quoting a taped conversation from November between the country’s pro-Musharraf attorney general and an unnamed man.

The attorney general had apparently been talking to a reporter,and while on that call,took another call,where he talked about vote rigging. The reporter had recorded the entire conversation. I scanned through the e-mail. “Nawaz,” I said. I had somehow slipped into calling the former prime minister by his first name. “have to hear this.” I then performed a dramatic reading of the message in full,culminating in the explosive direct quote from the attorney general,recorded the month before Bhutto was killed and just before Sharif flew home:“Leave Nawaz Sharif … I think Nawaz Sharif will not take part in the election … If he does take part,he will be in trouble. If Benazir takes part she too will be in trouble … They will massively rig to get their own people to win. If you can get a ticket from these guys,take it … If Nawaz Sharif does not return himself,then Nawaz Sharif has some advantage. If he comes himself,even if after the elections rather than before … Yes …” It was unclear what the other man was saying,but Human Rights Watch said the attorney general appeared to be advising him to leave Sharif’s party and get a ticket from “these guys,” the pro-Musharraf party,the massive vote riggers. Sharif’s aide stared at me openmouthed. “Is that true? I can’t believe that.” “It’s from Human Rights Watch,” I said. “There’s apparently a tape recording. Pretty amazing.” Sharif just looked at me. “How can you get a text message that long on your telephone?” “It’s an e-mail,” I said,slightly shocked that Sharif was unconcerned about what I had just said. “This is a BlackBerry phone. You can get e-mail on it.” “Ah,e-mail,” he said. “I must look into this BlackBerry.”

Sharif soon whipped out a comb,pulled the rearview mirror toward him,and combed his hair. I watched,fascinated. His hair plugs were in some ways genius—not enough to actually cover his bald spot but enough to make him seem less bald. He had the perfect hair transplant for a Pakistani politician who wanted to look younger while still appearing like a man of the people. But with every pull of the comb,I counted the potential cost—$1,000,$2,000. At the next speech,Sharif spoke in front of a metal podium with a bulletproof glass screen that ended three inches below the top of his head. I wondered if Musharraf was trying to kill him. The election was three days away. And as much as Sharif seemed to be slightly simple,he was also increasingly popular,largely because of his support of the deposed judges. While Bhutto’s widower campaigned on the memory of his dead wife,Sharif campaigned against Musharraf and for justice. Bhutto’s party would win the most votes.

But I thought Sharif would perform better than anyone suspected. The day of the election,two journalist friends and I drove to polling stations in Islamabad and neighboring Rawalpindi. Everywhere we heard the same name:Nawaz Sharif. It was rather spooky. At one point,we found a man who had spent the entire night cutting up white blankets,gluing them to his new car,and then painting them with tiger stripes. He finished the project off with black-feather trim. “What are you going to do if it rains?” I asked the man. “God willing,it won’t,” he said. I snapped a photograph with my BlackBerry. By the end of the day,the results were clear—Musharraf’s party had received barely any votes. Secular parties had triumphed over religious ones. Bhutto’s party had won the most seats,as predicted. But Sharif’s party had won the second-highest amount of votes,a surprise to many Western observers. Through the election,Sharif had exacted revenge on Musharraf. And Bhutto’s party needed Sharif to have enough seats to run the country. After more than eight years of political irrelevance,Sharif was back. I sent him a text message and asked him to call. A few hours later,he did,thrilled with his victory.

“I saw a car today,where a man had glued blankets to it and painted it like a tiger,” I told him at one point. “Really?” he asked. “Yeah. It was a tiger car.” He paused. “What did you think of the tiger car,Kim? Did you like the tiger car?” Weird question. I gave an appropriate answer. “Who doesn’t like a tiger car?”

“Capping the chaos,Nawaz Sharif then dropped out of the government. This shocked me—he had repeatedly threatened to end his party’s support for the coalition,but I didn’t think he would,as this chess move would in effect checkmate himself,eliminating any power he had. I called Sharif for the first time in months,and he invited me over to the Punjab House in Islamabad. He had always been unfailingly polite and soft-spoken with me. He seemed old-fashioned,speaking my name as a full sentence and rarely using contractions.

This time,in a large banquet hall filled with folding chairs and a long table,Sharif told his aides that he would talk to me alone. At the time,I barely noticed. We talked about Zardari,but he spoke carefully and said little of interest,constantly glancing at my tape recorder like it was radioactive. Eventually,he nodded toward it. “Can you turn that off?” he asked. “Sure,” I said,figuring he wanted to tell me something off the record. “So. Do you have a friend,Kim?” Sharif asked. I was unsure what he meant. “I have a lot of friends,” I replied. “No. Do you have a friend?” I figured it out. “You mean a boyfriend?” “Yes.” I looked at Sharif. I had two options—lie,or tell the truth. And because I wanted to see where this line of questioning was going,I told the truth. “I had a boyfriend. We recently broke up.” I nodded my head stupidly,as if to punctuate this thought. “Why?” Sharif asked. “Was he too boring for you? Not fun enough?” “Um. No. It just didn’t work out.” “Oh. I cannot believe you do not have a friend,” Sharif countered. “No. Nope. I don’t. I did.”

“Do you want me to find one for you?” Sharif asked. To recap:The militants were gaining strength along the border with Afghanistan and staging increasingly bold attacks in the country’s cities. The famed Khyber Pass,linking Pakistan and Afghanistan,was now too dangerous to drive. The country appeared as unmoored and directionless as a headless chicken. And here was Sharif,offering to find me a friend. Thank God the leaders of Pakistan had their priorities straight. “Sure. Why not?” I said. The thought of being fixed up on a date by the former prime minister of Pakistan,one of the most powerful men in the country and,at certain points,the world,proved irresistible. It had true train-wreck potential.

“What qualities are you looking for in a friend?” he asked. “Tall. Funny. Smart.” I envisioned a blind date at a restaurant in Lahore over kebabs and watermelon juice with one of Sharif’s sidekicks,some man with a mustache,Sharif lurking in the background as chaperone. “Hmmm. Tall may be tough. You are very tall,and most Pakistanis are not.” Sharif stood,walked past the banquet table toward the windows,and looked out over the capital. He pondered,before turning back toward me. “What do you mean by smart?” he asked. “You know. Smart. Quick. Clever.” “Oh,clever.” He nodded,thought for a second. “But you do not want cunning. You definitely do not want a cunning friend.” He looked out the window. It seemed to me that he was thinking of Bhutto’s widower,Zardari,his onetime ally and now rival,a man universally considered cunning at business who many felt had outsmarted Sharif in their recent political tango. “No. Who wants cunning?” “Anything else?” he asked. “What about his appearance?”

“I don’t really care. Not fat. Athletic.” We shook hands,and I left. In all my strange interviews with Sharif,that definitely was the strangest. ……

“The next night,Samad drove some friends and me to a dinner inside the diplomatic enclave. My phone beeped with a text message from a number with a British international code. “Hello,Kim,I arrived London yesterday. Congratulations on AZ becoming the new president,how is he doing and how have the people taken it? I am working on the project we discussed and will have the result soon. Best wishes and warm regards.” I had no idea who sent the message. My brother? Sean? No,this sender clearly knew me from Pakistan. And what was the project? What had I discussed? I read the text message to my friends,and we pondered the sender. Then,finally,I remembered reading that Nawaz Sharif had flown to London so that his sick wife could have some tests. “Is this Nawaz?” I replied. “You are correct,” he responded. The project. That was funny. Everyone in the car,even the man from the U.S. embassy,agreed that I needed to see this through. And I thought—well,we all did—how hilarious it would be if Sharif actually found an option that worked. ……

“I flew to India to write some stories. Nawaz Sharif asked for my number there. He needed to talk about something important,outside Pakistan. One early evening,he called from London. Sharif wondered whether I would be back in Pakistan before Eid al-Fitr,the Islamic holiday at the end of Ramadan. Maybe,I told him. He planned to go to Pakistan for a day,and then to Saudi Arabia for four days. “I am working on the project,” he said. “Day and night,I’m sure,” I replied. Sharif said the real reason he was calling was to warn me that the phones were tapped in Pakistan. “Be very careful,” he said. “Your phones are tapped. My phones are tapped. Do you know a man named Rehman Malik? He is giving the orders to do this,maybe at the behest of Mr. Zardari.” Everyone knew Rehman Malik,a slightly menacing figure who was the acting interior minister of Pakistan. He was known for making random word associations in press conferences and being unable to utter a coherent sentence. He also had slightly purple hair. “Is this new?” I asked. “Hasn’t it always been this way? “Well,yes. But it has gotten worse in the past two or three months.” So true. He had a solution—he would buy me a new phone.

And give me a new number,but a number so precious that I could only give it to my very close friends,who had to get new phones and numbers as well. Very tempting,but I told him no. He was,after all,the former prime minister of Pakistan. I couldn’t accept any gifts from him. “Sounds complicated. It’s not necessary. And you can’t buy me a phone.” He said I needed to be careful. We ended our conversation,and he promised to work on the project. “Don’t be—what is it you say? Don’t be naughty,” he said before hanging up. Naughty? Who said that? The conversation was slightly worrying. I thought of Sharif as a Punjabi matchmaker determined to find me a man,not as anyone who talked naughty to me. ……

“I planned a trip to Afghanistan,where the politics were much less murky,where the suicide bombers were much less effective,to write about alleged negotiations with the Taliban. That’s why I had to see Nawaz Sharif again. Emissaries from the Afghan government and former Taliban bigwigs had flown to Saudi Arabia for the feasts that marked the end of Ramadan. But they had another goal. Afghan officials had been hoping that the influential Saudi royal family would moderate negotiations between their battered government and the resurgent militants. Sharif,in Saudi Arabia at the time,was rumored to have been at those meetings. That made sense. He was close to the Saudi king. He had supported the Afghan Taliban,when the regime was in power.

I called Sharif and told him why I wanted to see him. “Most welcome,Kim,” he said. “Anytime.” We arranged for a lunch on a Saturday in October—I was due to fly to Kabul two days later. Samad and I decided to drive the five hours from Islamabad to Raiwind instead of flying. Samad showed up on time,but I overslept,having been up late the night before. I hopped out of bed and rifled through my Islamic clothes for something suitable because I liked to dress conservatively when interviewing Pakistani politicians. I yanked out a red knee-length top from India that had dancing couples embroidered on it. Potentially ridiculous,but the nicest clean one I had. We left Islamabad. “You’re gonna have to hurry,Samad,” I said. “Possible?” “Kim,possible,” he said. It always cracked me up when I got him to say that. We made good time south,but got lost at some point on the narrow roads to Raiwind. Sharif sent out an escort vehicle with flashing lights to meet us. We breezed through security—we actually didn’t even slow down—and I forced Samad to stop in the middle of the long driveway leading up to Sharif’s palace. I had forgotten to comb my hair or put on any makeup. I turned the rearview mirror toward me,smoothed down my messy hair with my hands,and put on some lipstick. Twenty seconds. “Good enough,” I pronounced my effort,and flipped the mirror back to Samad. We reached the imposing driveway.

Sharif actually waited in front of his massive front doors for me,wearing a blue suit,slightly snug around his waist. He clasped his hands in front of his belt. It was clear that our meeting was important. Sharif was surrounded by several lackeys,who all smiled tight-lipped before looking down at the ground. I jumped out of the car,sweaty after the ride,panicked because I was late. I shook Nawaz’s hand—he had soft fingers,manicured nails,baby-like skin that had probably never seen a callous. “Hello,Kim,” he said. “Hey,Nawaz. Sorry I’m late.” In the sitting room,I immediately turned on my tape recorder and rattled off questions. Was Sharif at the negotiations? What was happening? He denied being at any meetings,despite press reports to the contrary. I pushed him. He denied everything. I wondered why he let me drive all this way,if he planned to tell me nothing. At least I’d get free food. He looked at my tape recorder and asked me to turn it off. Eventually I obliged. Then Sharif brought up his real reason for inviting me to lunch. “Kim. I have come up with two possible friends for you.” At last. “Who?” He waited a second,looked toward the ceiling,then seemingly picked the top name from his subconscious. “The first is Mr. Z.” That was disappointing. Sharif definitely was not taking this project seriously. “Zardari? No way. That will never happen,” I said. “What’s wrong with Mr. Zardari?” Sharif asked. “Do you not find him attractive?”

Bhutto’s widower,Asif Ali Zardari,was slightly shorter than me and sported slicked-back hair and a mustache,which he was accused of dying black right after his wife was killed,right before his first press conference. On many levels,I did not find Zardari attractive. I would have preferred celibacy. But that wasn’t the point. Perhaps I could use this as a teaching moment. “He is the president of Pakistan. I am a journalist. That would never happen.”

“He is single.” Very true—but I didn’t think that was a good enough reason. “I can call him for you,” Sharif insisted. I’m fairly certain he was joking.

“I’m sure he has more important things to deal with,” I replied.

“OK. No Mr. Z. The second option,I will discuss with you later,” he said. That did not sound promising. We adjourned our meeting for lunch in the dining room,where two places were set at a long wooden table that appeared to seat seventy. We sat in the middle of the table,facing each other over a large display of fake orange flowers. The food was brought out in a dozen courses of silver dishes—deep-fried prawns,mutton stew,deep-fried fish,bread,a mayonnaise salad with a few vegetables for color,chicken curry,lamb. Dish after dish,each carried by waiters in traditional white outfits with long dark gray vests. Like the good Punjabi that Sharif was,he kept pushing food on me. “Have more prawns. You like prawns,right?” He insisted on seconds and thirds. It felt like a make-believe meal.

I didn’t know which fork to use,not that it mattered in a culture where it was fine to eat with your hands,but the combination of the wealth,the empty seats,and the unspoken tiger in the room made me want to run screaming from the table. I needed to get out of there. “I have to go.” “First,come for a walk with me outside,around the grounds. I want to show you Raiwind.” “No. I have to go. I have to go to Afghanistan tomorrow.” Sharif ignored that white lie and started to talk about where he wanted to take me. “I would like to take you for a ride in the country,and take you for lunch at a restaurant in Lahore,but because of my position,I cannot.” “That’s OK. I have to go.” “I am still planning to buy you a phone. Which do you like Nokia,iPhone?” So now he knew what a BlackBerry was. But I would not bend. “You can’t buy me a phone,” I said. “Why not?” “You’re the former prime minister of Pakistan. No.” “Which do you like?” He kept pressing,wouldn’t let it go. BlackBerry,Nokia,iPhone,over and over. That scene from The Wizard of Oz started running through my head:Lions and tigers and bears,oh my! “BlackBerry,Nokia,or iPhone,Kim?” “The iPhone,” I said,because I already had a Nokia and a BlackBerry. “But I still can’t take one from you.” As we left,Samad insisted on getting our picture taken with Sharif. Samad was a Bhutto man,which meant he should have been a Zardari man,but increasingly,like many of Bhutto’s followers in Pakistan,Samad had grown disenchanted with Zardari. And increasingly,Samad liked Sharif. Everyone liked Sharif. Behind the scenes,the tiger of Punjab was growing very powerful. His decision to break with Zardari over the issue of restoring the judges had proved to be smart. As Zardari’s government floundered and flip-flopped,Sharif looked more and more like an elder statesman. Regardless,I told my boss it was no longer a good idea for me to see Sharif. He was married,older,rich,and powerful. As a pleasant-looking,pedigree-lacking American with hair issues,I was an extremely unlikely paramour. But Sharif had ended our visit with a dangling proposition—the mysterious identity of a second potential friend. I decided to stick to a tapped-phone relationship. ……

“And I knew,with plenty of reservations,that I needed to go to Lahore because of Nawaz Sharif. If anyone knew the right Faridkot,he would. That Friday,Pakistan seemed to have launched its typical crackdown on the charity—in other words,lots of noise,little action. A charity billboard in the heart of Lahore proclaimed:“We can sacrifice our lives to preserve the holiness of the Prophet.”

I sent my translator into the group’s mosque because I wasn’t allowed. There,flanked by three armed guards,the founder of Jamaat-ud-Dawa and Lash preached to about ten thousand men. His bluster was typical Islamic militant stuff—about sacrifice,about Eid al-Adha,the upcoming religious festival where devout Muslims would sacrifice an animal and give part of it to the poor. The holiday honored Ibrahim,or as Jews and Christians knew him,Abraham. “Sacrifice is not just to slaughter animals in the name of God,” the founder said. “Sacrifice also means leaving your country in the name of God. It means sacrificing your life in the name of God.” His meaning seemed fairly clear.

Meanwhile,the spokesman for the charity tried to rewrite history. He said the founder was barely involved with Lash—despite founding it—and insisted Lash was now based in India. The spokesman also drew a vague line in the sand,more like a smudge—he said the charity talked about jihad,but did not set up any training camps for jihad. The man who ran the ISI when Lash was founded denied having anything to do with the group. “Such blatant lies,” he told me,adding later that Jamaat-ud-Dawa was “a good lot of people.”

These men seemed convinced of their magical powers,of their ability to wave a wand and erase a reporter’s memory. This obfuscation was not even up to Pakistan’s usual level. With a heavy heart,I knew I needed to see Nawaz Sharif. I figured I might be able to get something out of him that he didn’t know he wasn’t supposed to tell me—as former prime minister,he’d certainly be told what was happening,but because he wasn’t a government official,he wouldn’t necessarily know that he was supposed to keep the information quiet. But this time,I planned to bring my translator along,a male chaperone. Samad drove our teamout to Raiwind. I sat in the back of the car,writing up my story about the charity on my computer,trying not to think about what Sharif might try to pull this visit. Eventually,we walked inside Sharif’s palace.

Sharif looked at my translator,then me,clearly confused. He invited us both into his computer room,where we sat on a couch. Sharif sat on a chair,near a desk. When he answered my questions,he stared at my translator. My translator,embarrassed to be there,stared at the ground. Sharif told me the right Faridkot—the one in Okara district,just a couple of hours from Lahore. He gave me the phone number for the provincial police chief. He told me what Indian and Pakistani authorities had told him about the lone surviving militant.

For us,this was big news—a senior Pakistani confirming what the government had publicly denied:The attackers were from Pakistan. “This boy says,‘I belong to Okara,and I left my home some years ago,’ ” Sharif said,adding that he had been told that the young man would come home for a few days every six months or a year. “He cut off his links with his parents,” Sharif also told me. “The relationship between him and his parents was not good. Then he disappeared.”

Once the interview was finished,Sharif looked at me. “Can you ask your translator to leave?” he asked. “I need to talk to you.” My translator looked at me with a worried forehead wrinkle. “It’s OK,” I said. He left. Sharif then looked at my tape recorder. “Can you turn that off?” I obliged. “I have to go,” I said. “I have to write a story.” He ignored me. “I have bought you an iPhone,” he said. “I can’t take it.” “Why not? It is a gift.” “No. It’s completely unethical,you’re a source.” “But we are friends,right?” I had forgotten how Sharif twisted the word “friend.” “Sure,we’re friendly,but you’re still the former prime minister of Pakistan and I can’t take an iPhone from you,” I said. “But we are friends,” he countered. “I don’t accept that. I told you I was buying you an iPhone.” “I told you I couldn’t take it. And we’re not those kind of friends.” He tried a new tactic. “Oh,I see.

Your translator is here,and you do not want him to see me give you an iPhone. That could be embarrassing for you.” Exasperated,I agreed. “That’s it.” He then offered to meet me the next day,at a friend’s apartment in Lahore,to give me the iPhone and have tea. No,I said. I was going to Faridkot. Sharif finally came to the point. “Kim. I am sorry I was not able to find you a friend. I tried,but I failed.” He shook his head,looked genuinely sad about the failure of the project. “That’s OK,” I said. “Really. I don’t really want a friend right now. I am perfectly happy without a friend. I want to be friendless.” He paused. And then,finally,the tiger of Punjab pounced. “I would like to be your friend.” I didn’t even let him get the words out. “No. Absolutely not. Not going to happen.”

“Hear me out.” He held his hand toward me to silence my negations as he made his pitch. He could have said anything—that he was a purported billionaire who had built my favorite road in Pakistan,that he could buy me a power plant or build me a nuclear weapon. But he opted for honesty. “I know,I’m not as tall as you’d like,” Sharif explained. “I’m not as fit as you’d like. I’m fat,and I’m old. But I would still like to be your friend.” “No,” I said. “No way.” He then offered me a job running his hospital,a job I was eminently unqualified to perform. “It’s a huge hospital,” he said. “You’d be very good at it.” He said he would only become prime minister again if I were his secretary. I thought about it for a few seconds—after all,I would probably soon be out of a job. But no.

The new position’s various positions would not be worth it. Eventually,I got out of the tiger’s grip,but only by promising that I would consider his offer. Otherwise,he wouldn’t let me leave. I jumped into the car,pulled out my tape recorder,and recited our conversation. Samad shook his head. My translator put his head in his hands. “I’m embarrassed for my country,” he said. After that,I knew I could never see Sharif again. I was not happy about this—I liked Sharif. In the back of my mind,maybe I had hoped he would come through with a possible friend,or that we could have kept up our banter,without an iPhone lurking in the closet. But now I saw him as just another sad case,a recycled has-been who squandered his country’s adulation and hope,who thought hitting on a foreign journalist was a smart move. Which it clearly wasn’t.

The next morning,Samad drove us to Faridkot. As soon as we pulled into town,dozens of men in cream-colored salwar kameezes flanked our car. One identified himself as the mayor—he denied all knowledge of the surviving militant and his parents. Other Pakistani journalists showed up—we had all found out about the same time that this was the Mumbai assailant’s hometown,a dusty village of ten thousand people in small brick houses along brick and dirt paths. My translator said many of the cream-attired men here were ISI. Another journalist recognized an ISI commander. Their job:to deny everything and get rid of us. ……

“I packed up my belongings and got ready to fly home. The day I planned to execute my exit strategy,my phone rang. And the caller was the other eccentric older man who had dominated my time,from the other side of the border. Nawaz Sharif. His timing was always impeccable. “Is this Kim?” he asked. “Yes,” I said,shoving Afghan tourism guides from the 1970s into a suitcase. I was hesitant,unsure of what he wanted. “So. It’s been a long time,” he said,awkwardly. “What are your plans to come to Pakistan?” “Actually,I’m moving back to the U.S. New York,in fact. I’m leaving in a few hours.”

“Oh,congratulations. I will have to come see you when I’m in New York,” he said. “That would be great,” I replied. “We’re still friends,right?” he asked,tentatively. “Always,” I said. “We’ll stay friends,right?” he said. “Sure.” We said goodbye. I had about the same level of intention of being friends with Nawaz Sharif as I did with Sam Zell. But I figured I could just end our relationship through the inevitable ennui of distance and time,and through the likelihood that he would never get his hands on my U.S. number. (He was more resourceful than I thought).