Moeed Pirzada | Khaleej Times |

CALL it irony or comedy but the fact is that at its 61st anniversary Islamic Republic of Pakistan, that has always used the stick of religion to fight all separatist tendencies, now faces an Islamic threat to the survival of the state. Is there a limit to the jokes history can play? But then all of us have heard of Dr. Strangelove and black comedy. Prof. Michel Chossudovsky’s paper ‘The Destabilisation of Pakistan’ that first appeared after Benazir Bhutto’s death has become a must read in Pakistan. Could it be just a coincidence that in the last few weeks I found many a civil servant, army officers and media managers diligently pouring over it, often carefully with pencils in hands? Many others have kept copies on their office tables as part of their reading wish list.

Chossudovsky, a professor of economics at Montreal University, loves shocking his readers. Citing US National Intelligence Council and CIA (NIC-CIA) reports of 2005 he first explains the US strategic thinking of reconfiguring Pakistan, and then brings out futuristic maps, according to him being used by Pentagon for war games, that show an independent Baluchistan and large tracts of Pakistani NWFP and tribal areas incorporated in an expanded Afghanistan. This might have been scary enough for most people but he insists that the US may be providing covert support to some of the Islamic terrorists operating inside Pakistan to keep the pot burning to increase the ethnic, social and factional strife and to provide excuses for its own stay in Afghanistan and the region.

Interestingly, Chossudovsky’s rather colourful and overactive mental bladder looks heavily dependent upon the academic flows and streams of thought from Professor Stephen Cohen, America’s foremost scholar and policy expert on South Asia. Cohen in his 2004 book, Idea of Pakistan, while discussing the potential separatist threats to the Pakistani state had dealt at length the possibility of a Pashtun movement for independence egged on by Afghanistan and in time supported by India.

This week Cohen was a guest of Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT) and we got the opportunity to sit for an exclusive interview for Geo TV. I asked Prof. Cohen of the possible plans and conspiracies afoot to destabilise Pakistan. Denying vociferously that the US can ever be part of any such moves against Pakistan he nevertheless agreed that other regional players may be involved. But he insisted that whatever they may do the Islamic extremists in Pakistan’s tribal areas represent a clear and present danger in their own right. And there is no denying that he has a point.

The fact is: ever since the 1971 creation of Bangladesh — as a result of political failure, civil war and Indian intervention — Pakistanis remain mortally afraid of any secessionist tendencies that may arise and the congenital enemies of Pakistan are continuously waiting, now for almost 37 years, for more break ups to happen.

These natural fears and dark hopes may be somewhat exaggerated for most new and developing states that continue to suffer from such centrifugal tendencies. And since the creation of Bangladesh, Pakistani state has successfully fought and warded off separatist movements in Baluchistan and Sindh.

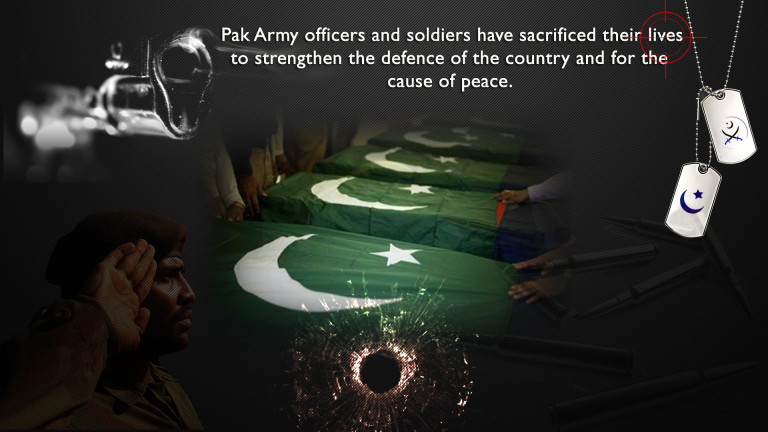

However, the repeated Islamist mini-insurgencies in the federally-administrated tribal areas bordering Afghanistan — by obscure mullahs that sport beards of various sizes and possess state-of-the-art encryption technologies — are giving a new meaning to these historic fears and hopes. Fortunately or by design, the tribal insurgents, at least so far, have not demanded independence in unambiguous geographical terms. What they often demand is enforcement of Sharia law or the freedom to fight infidel Americans in the neighbouring Afghanistan. In other words what they want are separate ways and lives.

But the problem is: political configurations are like marriages. Any marriage to continue will need both partners — or in case of mullahs all five partners — to have a common world view. Once a common world view fails, or falters, most marriages — except of feudal and tribal cultures — end, unless you want to keep the other partner with a shot gun pointed at head or still better: chained in the basement. Islamist insurgents’ separate world view leaves Pakistani state with no real options except to fight them out in the short run and conquer the minds of their children.

Bangladesh separation in 1971 lead to the repeatedly asserted political aphorism that Islam was a weak bond or glue for state building. And many of those who publish maps of a reconfigured Pakistan, within the US, are relying upon the assumption that a break up into pure ethnic units guarantees greater stability. They are wrong, for there may be elements of truth in the mid-twentieth century paradigms but then the recent struggle inside Pakistani periphery is more complex; if anything this is a contest inside the mind of Islam between those who are exposed to modernity and those who have been left behind in the medieval age.

The assumption of all those who once fervently thought that Islam can be a unifying force was that one God, one book and one prophet provides a common ground for a shared world view. That may not be totally untrue and could certainly provide a basis to build something where nothing exists, but in this age of globalisation and You-tube much more is needed for sustaining a marriage — civil or political — than a simple agreement on basics.

Today Muslims living across the world have different world views, often sharing little beyond grievances against the West. Even within Pakistan world view differs from city to city but, however different it may be, it still has strong common themes that bind people like different coloured beads in a string. But Pakistani state, in the last 61 years, due to its administrative style, inherited from the British, failed to offer structures in the tribal areas that could have connected them with the rest of Pakistan beyond the historic bond of Islam.

No wonder tribal cultures have been left in a time warp, sharing little with the rest of Pakistan — except the age-old narrative of Islam, and a perennial distrust of the West. And here lies the communication challenge.

The events of the last few weeks, from Afghanistan to Bangalore to Kashmir, have made it obvious that the mutual accommodation which India and Pakistan had negotiated with each other in 2003-04 has broken down. Whosoever is at fault, there is no option but to come to a new arrangement. Islamabad needs India to stop meddling in its tribal areas, whatever quid pro quo it may take. But once it gets the political breathing space it has to work on developing the structures that provides the common world view. If it again failed, then Michel Chossudovsky’s maps and NIC-CIA reports will start to make increasing sense.